NOTE: This experiment is written for a lab set that includes a piece of

thin plywood and push pins. Your materials might not include these items.

In this case the following substitutions are suggested:

- Instead of the plywood you can use a piece of cardboard; the cardboard

should be at least a foot long and 8 inches wide. The stresses

involved are small (less than a pound), so medium-weight cardboard is more

than sufficient; lighter weights are often OK, but if the cardboard is too

light it might bend.

- If you have push pins of your own you should use them, but if they

aren't handy it's not difficult to fold three paperclips into U shapes to

make three 'staples', which can then be pushed through the cardboard to hold

the ends of the three rubber bands (if you do this be careful; it takes

moderate force to push a paper clip through cardboard, and if you have a

hand or finger helping out on the other side you can draw blood when the end

pushes through). To hold the system stable you'll want to push them

all the way through.

Whatever you use (plywood, cardboard, etc.), you'll want to support it above

your tabletop, in order to avoid damaging the tabletop. A cardboard box

works very well for this purpose; so would a couple of books to support the ends

of the board.

Set up the experiment:

1. Print out the

grid, which should give you a

printout with 1-cm squares. Place this grid on the plywood square. (Place an

accurate ruler on the grid and verify that the squares indeed line up with the 1-cm

marks. If they don't email the instructor and include the number of millimeters, to

the most accurate fraction of a mm you can estimate, by which the grid is off on a 10-cm

measurement in the horizontal direction, and the number of mm of error on a 10-cm

measurement in the vertical direction.)

You may also print out a page of

rulers. Be sure to

right-click on the page with the rulers, then click on Print. Otherwise you might

print out the top frame of the page, which is not what you want here. These rulers

should be accurate to within a fraction of a millimeter over their 22-cm length.

Measure them and be sure they are indeed accurate. Note that the markings on these

rulers might not be perfect, due to limitations of pixel placement, and that this

may introduce an additional small element of uncertainty in the results of your

measurements.

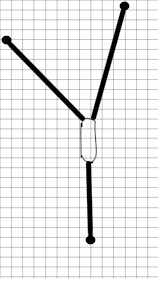

2. Using a paper clip, three rubber bands and three push pins

(or paperclip 'staples') set up the system

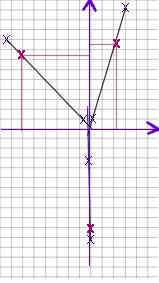

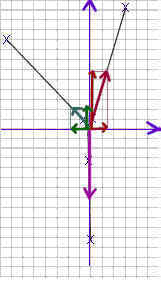

as shown in the figure below. In the figure the dark thick lines represent the

rubber bands, all three of which are attached directly to the paper clip. The small

circles at the other end of each rubber band represents a push pin (or a

'staple'). The setup should

have the following characteristics:

- One rubber band (the one lowest in the figure below) should run along one of the

vertical lines of the grid. In the figure the lowest rubber band isn't quite

parallel to the vertical line. Make sure yours is parallel and that it's on the

line.

- Don't let any rubber band exceed its original length by more than 30%

(e.g., a rubber band with unstretched length 8 cm should not exceed 10.4 cm in length). The

rubber band most likely to exceed

this length will be the one parallel to the vertical grid lines. Keep an eye on that one

as you position the other two. It would be a good idea to check your

calibration graphs to see which rubber band is capable of exerting the most

force at the 'plus-30% length', and use that for the 'vertical' rubber band.

- The second rubber band will be directed toward the upper left and will

be angled at least 45 degrees to the left of vertical. This rubber

band should stretched to a length that will cause it to exert a force of

about 1 Newton.

- The third rubber band should exert enough force to cause the lower rubber band to

stretch to at least 20% beyond its maximum unstreched length, but not more

than 30% (standard #32 or #33 rubber bands with an initial length of about 8

cm stretch to about 10 cm when supporting about 2 Newtons of weight;

if your rubber bands are shorter or stiffer, the lengths may be shorter).

The third rubber band will probably

end up closer to vertical than the second rubber band. Remember that the lower

rubber band has to be parallel to the vertical lines.

- It's not shown that way in the picture but you should use paper clips bent into hooks to

attach the rubber bands to the push pins. That will prevent the push pins from

'crushing' the rubber bands and preventing the ends from stretching, and it will also make

it much easier to accurately mark the positions of the ends of the rubber bands.

However the 'hooks' can't be too long, or the system won't fit on the board.

(If you use paperclip 'staples', as described near the beginning, there is

no need to use these 'hooks').

Be very sure that the 'downward' rubber band is stretched to between 10.0 and 10.5 cm,

and that it is parallel to the vertical gridlines.

Mark the positions of the ends of the rubber bands, measure their lengths and determine

the force exerted by each:

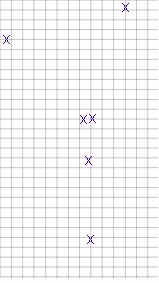

1. Using a pencil with a good point or a reasonably fine-tipped pen make an x

under the end of each rubber band, with the x crossing directly under the very end of the

rubber band. Locate this mark as accurately as possible. The first figure below

indicates the positions of the x's (note that the x's under the circles representing push

pins will in fact be under hooks at the ends of the rubber bands).

2. Once you have marked both ends of each rubber band all your information will

be on the grid, and you may remove the pins, the rubber bands and the paper clip.

The second figure above shows the grid as it would be with just the x's marked.

3. Using a ruler measure the length, in cm, of each rubber band,

based on the distance between your marked points.

4. Using the appropriate calibration graph or calibration function determine the

force exerted by each rubber band.

In the box below give the length of each rubber band and the corresponding

force in Newtons, in this order and separated by a comma:

- In the first line give the information for the 'vertical' rubber band.

- In the second line give the information for the rubber band which slopes

up and to the left..

- In the third line give the information for the rubber band which slopes up

and to the right.

Starting the fourth line give a brief explanation, in your own words, of

what the numbers you have reported mean and how you determined your forces.

Your forces should correspond to the lengths of the individual rubber bands, as

indicated by the calibration graph you did for each in the Rubber Band

Calibration experiment.

We will now proceed to calculate the components of the net force using three

different methods. The methods are:

- Graphical determination of force components using sketches of the

vectors and projection lines.

- Graphical determination of the resultant vector using the polygon method

of vector addition.

- Calculation of components using basic trigonometry (methods of

Introductory Problem Set 5).

Graphically determine the components of your forces, using sketches and

projection lines:

Set up coordinate axes on the grid, select a point on each line and draw projection

lines to determine coordinates; use coordinates to determine angles:

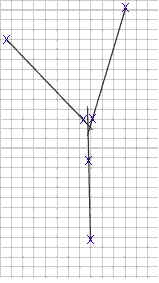

1. Find the point at which the lines of force meet. For each rubber band use a

straightedge to draw a line along the center of the rubber band's

position.

Extend all three lines to their point of intersection. The first figure below

illustrates the lines corresponding to the above figures.

2. Construct a y vs. x coordinate system whose origin is at the point where the

three lines of force intersect, as shown in the second figure below.

3. Locate on each line of force the point which is 10 cm from the intersection

(i.e., the origin of the coordinate system),

as indicated by the heavy red x's in the first figure below. For each

rubber band, just measure 10 cm from the origin, along the line of force.

4. Sketch the projection line from each of these points to the x and y axes, as

shown in the second figure below. Since one point is already on the y axis it isn't

necessary to sketch its projection lines.

5. Determine the x and y coordinate of the point selected on each line of force.

For example in the picture the x and y coordinates of the line in the first

quadrant are about 2.3 cm and 8.5 cm, so the point is (2.3, 8.5). Note that the point

(2.3, 8.5) isn't really 10 cm from the origin; when you located your points you hopefully did much

better.

Report your results in the box below, x and y in centimeters in

comma-delimited format, one rubber band to a line. Report with the

rubber bands in the same order you reported previously.

Starting in the fourth line, give a brief explanation of how you

constructed this graph and how you obtained

your results.

************

6. Find the angle of each line of force by calculating the inverse tangent of the

y coordinate divided by the x coordinate (this means inverse tangent of (y

coord / x coord), making sure your calculator is in degree mode.

For example, for the point (2.3, 8.5) we would get an angle equal to arctan(8.5 / 2.3) =

74.9 degrees, approximately.

On a calculator you can use the inverse tangent function (usually INV and TAN keys, or

2d function and TAN). Be sure you are in degree mode if you want the angle in

degrees, or in radian mode if you want the angle in radians.

If you use Excel you can use the ATAN function (for this angle you would type =ATAN(8.5

/ 2.8) into a cell). Excel gives angles in radians, which you can convert to degrees

if you multiply by 180 / `pi (you could just type in = ATAN(8.5 / 2.8) * 180 / PI(), which

will give you the angle in degrees. Note that pi() is Excel's way of denoting `pi).

7. Find the angle made by each force vector with the positive x axis, as

measured in the counterclockwise direction from the positive x axis.

Note that the angle you found in the preceding instruction is the angle of

the line of force with the x axis.

- The actual force vector might point in either direction along this

line.

For example, a line at angle 60 degrees might indicate a force vector

into the first quadrant, at 60 degrees as measured counterclockwise from

the positive x axis; or the force vector might also point into the third

quadrant, making its angle 240 degrees.

Similarly a line at angle -30 degrees could indicate a vector into

the fourth quadrant, at -30 degrees or equivalently at 330 degrees; or

it could indicate a vector into the second quadrant, at angle 150

degrees.

- The rule for the angle of the line with the x axis is arctan(y

component / x component). The angle of a vector (which as

indicated above can point in either of two directions along the line) is

arctan ( y component / x component), plus 180 deg if the x component is

negative.

Report your angles in the box below, one to a line, reporting the rubber

bands in the same order as before. This will require the first three

lines.

Starting in the fourth line explain briefly, in your own words, how you

obtained your angles.

As we move counterclockwise around the origin, starting from the positive x

axis, we pass the positive y axis as our angle passes through 90 degrees;

between 0 and 90 degrees our vector is directed into the first quadrant.

Continuing to move counterclockwise, we encounter the negative x axis at 180

deg, the negative y axis at 270 deg and the positive x axis at 360 deg.

The second quadrant runs from 90 deg to 180 deg, the third quadrant from 180 deg

to 270 deg and the fourth quadrant from 270 deg to 360 deg.

Your first direction vector has x component zero, so arctan(y comp / x comp)

won't work. When the x component is zero and the y component isn't, it

should be clear that the vector is directed either upward or downward along the

y axis, which makes the angle either 90 deg or 270 deg. In this case it is

clear that the vector is directed downward, in the 270 degree direction.

The second vector (which if you have followed instructions is the one

that slopes up and to the left) is in the second quadrant, with a negative x

component and a positive y component. Arctan(y comp / x comp) yields a

negative angle. This is the correct angle of the line of force with

the x axis; however the line of force extends infinitely in both directions,

down into the fourth quadrant and back up into the second quadrant. The

actual force vector might point in either direction along this line, and in

this case the force vector points into the second quadrant.

-

For example, a line at angle 60 degrees might indicate a force

vector into the first quadrant, at 60 degrees as measured

counterclockwise from the positive x axis; or the force vector might

also point into the third quadrant, making its angle 240 degrees.

-

Similarly a line at angle -30 degrees could indicate a vector into

the fourth quadrant, at -30 degrees or equivalently at 330 degrees; or

it could indicate a vector into the second quadrant, at angle 150

degrees.

-

The rule for the angle of the line with the x axis is arctan(y

component / x component). The angle of a vector (which as indicated

above can point in either of two directions along the line) is arctan (

y component / x component), plus 180 deg if the x component is negative.

Since the x component of your second vector is negative, you need to add

180 deg to the angle given by the arctan. Your angle will then fall

between 90 deg and 180 deg, consistent with the direction of the vector you

sketched.

8. Verify that all your points were really 10 cm from the origin by using the

Pythagorean Theorem; i.e., by calculating `sqrt( x^2 + y^2 ), where x and y are the

coordinates of the points. For the point (2.3, 8.5), for example, you would get

`sqrt( 2.3^2 + 8.5^2) = 9.2, approx.. The result should be 10. Obviously

whoever located the point on the above graph didn't do a very good job. Hopefully

your results will be better.

Give the results of the Pythagorean theorem in the box below, reporting in

each line, in comma-delimited format, the result you obtained and its

deviation from the ideal 10 cm. Report three lines, one for each

rubber band, reporting in the same order as previously.

Starting in the fourth line explain what the numbers you have reported

mean and how they were obtained.

Results are typically with about 3% of 10 cm (i.e., between .97 cm and 1.03 cm).

For example, if the components were 7.8 and 6.1, the length would be sqrt(7.8^2

+ 6.1^2) = 9.9, approx.

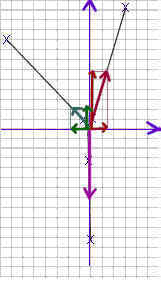

Draw to scale the force vectors corresponding to the rubber band forces, determine

their components and find their sum. Note carefully that you are

drawing force vectors here, NOT the lengths of the rubber bands. You are

now done

with the lengths of the rubber bands. Those lengths were only used to find the

forces and they are no longer important.

1. Using a scale of 4 cm per Newton sketch the vector representing the force

exerted by each rubber band (the force, not the length of the rubber band). Use a

different color or style for the vector corresponding to each rubber band; you might use

pens of different colors, or you might use pencil for one, pen for another, and another

pen with a different color; or you could use a line which is thicker or

thinner than the other lines..

2. Each vector should have its initial point at the origin, should lie along the

line of force and be directed in the direction of the force exerted on the

paper clip by the rubber band. The first figure below illustrates three

vectors representing forces of roughly 1.5 Newtons, .6 Newtons and 1.8 Newtons.

3. Now draw the projection lines, sketch the component vectors, and

validate the components as calculated using the sines and cosines of the

angles: From the tip of each vector

sketch the projection lines back to the x axis and to the y axis. Be sure the projection

lines run parallel to the grid lines and use a straightedge to locate the projection lines

as accurately as possible.

4. Using the same colors and/or line styles you used to sketch the vectors,

sketch the component of each of the force vectors along the x and y axes, as shown in the

second figure below.

5. Measure the length of each of these components, and using the 4 cm to 1 Newton

scale determine as accurately as possible how many Newtons are represented by each

component. In the figure below, for example, it looks like the red vector in the first quadrant

has components measuring 1.4 cm in the x direction and about 5.8 cm in the y

direction. These forces would correspond to .35 Newtons and 1.45 Newtons.

Enter your measurements in the box below. In each line enter 4

numbers, the first and second being the x and y components of your sketches,

in cm, and the second and third being the corresponding x and y forces.

Enter one line for each rubber band, using the same order of rubber bands as

before. Note each quantity you report will be positive or negative,

depending on whether that quantity is in the direction of the corresponding

axis or opposite the direction of that axis (i.e., right and left are + and -,

respectively; up and down are also + and - respectively).

Starting in the fifth line explain briefly what you numbers mean and how

you obtained them.

******

In the box below, report in the first line the total of the x components of

all your forces, and in the second line the total of the y components of all

your forces. In the third line explain how you obtained these totals and

show the numbers you added to obtain each.

The x component of your first vector (the one directed vertically downward)

should have been zero. The x components of your second and third vectors

should have been negative and positive, respectively. Ideally these

components would add up to zero, though because of significant uncertainty in

this experiment it is unlikely that they do.

The y component of your first vector is negative; the y components of the other

two are positive. Ideally the y components would add up to zero, but again

experimental uncertainties are great enough that they probably don't.

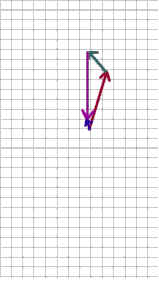

Graphically determine the vector sum by constructing a polygon

Add the three vectors by the polygon method:

1. Again sketch your three force vectors, this time arranged to form a polygon.

Let the terminal point of each vector be the initial point of the next. That is, the

vectors should be connected head to tail, as illustrated in the second figure below.

In this figure he polygon runs along the 'red' vector from (0, 0)

to (1.4, 6), then from this point along the 'green' vector to about (-.3,

8), then from this point along the 'purple' vector to about (-.3, 1).

At a scale of 4 cm per Newton, which can also be expressed as 1/4 Newton

per cm or .25 Newton per centimeter, the resultant vector has x component

-.3 cm * .25 N / cm = -.075 N and y component 1 cm * .25 N / cm = .25 N.

2. Now sketch a vector from the initial point of the first vector to the terminal

point of the last vector. This vector is the short blue vector in the second and third

figures below. The 'blue' resultant vector originates at (0, 0) and

terminates at the third point of the polygon, which we have estimated in the

figure below to be at (-.3, 1).

The fourth figure below indicates the components of this resultant

vector, about -.3 cm in the x direction and about 1 cm in the y direction..

What are the coordinates of the resultant vector in your sketch?

Give the x and y coordinates of the points on your actual graph, in cm,

then the x and y coordinates of the corresponding force components, in Newtons,

in the first line of the box below, in comma-delimited format.

Starting in the second line give a brief description of your polygon,

including the initial and terminal points of each of the vectors in the

polygon, and explain how you calculated the force components of your

resultant vector using the scale of the graph.

Your sketch should depict a triangle similar to the one shown here, though it

might not end up as close to the origin as in the above sketch.

Experimental uncertainties are random, so the tip of the final vector could end

up either above or below the origin, and either to the right or left.

3. Are the components of your resultant vector reasonably consistent with the

results you got in the preceding activity when you added the components of the vectors?

Answer in the box below.

*********

4. What is the magnitude of the force vector indicated by your

sketch? Use the pythagorean theorem to calculate the magnitude of the

resultant force vector, as indicated by the components you gave in the

preceding box. Give your magnitude in the first line, the magnitude calculated by the Pythagorean Theorem in the second, and explain

starting in the third line how you calculated it:

Use sines and cosines to find the components of the resultant vector and

compare with the results of graphical methods:

Add the three vectors by calculating components:

1. For each rubber band use the magnitude and the angle of the force it exerts to

determine the x and a y component of that force.

- Use the methods of Problem Set 5, using magnitude with the sine and cosine of each angle;

i.e., the x component of a force is F cos(theta) and the y component is

F sin(theta), where F is the magnitude and theta the angle of the force;

you listed these magnitudes and angles early in your report.

List in the box below, using

comma-delimited format, the magnitude, angle, x component and y component of

each vector. List one vector per line, in the order of rubber bands used

throughout this experiment. Starting in the third line explain in detail

how you calculated the components of the second of these vectors:

The magnitude of each vector is the force in Newtons, and the angle is the angle

you calculated earlier using the arctangent rule.