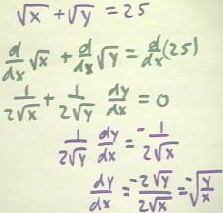

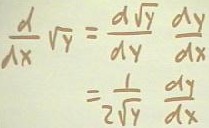

In the example below we apply implicit differentiation to the equation `sqrt(x) + `sqrt(y) = 25 to obtain an expression for dy / dx. Noting that d `sqrt(y)) / dx = d(`sqrt(y)) / dy * dy / dx, by the chain rule, we see in the second figure below that the derivative is 1 / (2 `sqrt(y)) * dy / dx. The other steps or straightforward, and are shown in the first figure below.

In the next example we calculate dy /dx implicitly from the equation e^(x^2) + ln y = 0. Noting, as in the second figure below, that the chain rule tells us that the derivative of ln(y) is 1/y * y', we follow straightforward steps in the first figure obtain y' = - 2 x y e^(x^2).

In the figure below we calculate dy / dx implicitly from the given equation. After the first step, in which we are careful to include the chain rule term y' = dy / dx whenever we take the derivative of a function of y, we collect all the terms containing y' as a factor on the left-hand side and factor out the y'. We then simplify the coefficient of y' by putting everything in that coefficient over the common denominator 1 + y^2; we can then multiply both sides of equation by the reciprocal of this coefficient to obtain our expression for y'. (Note that the same thing would have been accomplished and we multiplied every term in either the second or the third step by (1 + y^2), the one denominator that appears in the equation; this is generally a good strategy in any equation involving denominators).

In the next example we calculate the equation of the tangent line of the given function at the point (-1, 1).

Before differentiating implicitly, we simplify the form of equation by multiplying both sides by the denominator of the right-hand side, then using the distributive law to obtain and equation involving three distinct terms. In this way we avoid the more complicated algebra and resulting pitfalls of the quotient rule in favor of differentiating simple expressions involving no more than the product rule.

In the fourth and fifth steps below we perform the implicit differentiation. In the sixth step we collect all the terms involving y' as a factor on the left-hand side and factor out the y'. In the last step we divide both sides by the coefficient of y' to obtain the desired result.

We next to proceed to determine the equation of the desired tangent line. We begin by calculating the derivative y' at the point (-1, 1). The calculation is straightforward and we end up with y' = -7 / -11 = 7/11.

We then sketch a figure indicating the point (-1, 1) and a line through this point having slope 7/11. If (x, y) is a point on this line, then the slope between (-1, 1) and (x, y) is rise / run = (y - 1) / (x - (-1)) = (y-1) / (x+1); setting the slope equal to 7/11 we obtain the slope = slope equation, which we solve for y to obtain the standard slope-intercept equation of attention line.

We note that there is no other good way to determine the equation of this tangent line. We could attempt to solve the original equation for y, after which we could take the derivative. But when we do we obtain a cubic function for y. There is in fact a fairly complicated, is straightforward, process for finding the factors of the cubic equation, but it is a whole lot more trouble than implicit differentiation.

Tangent Line Approximations and l'Hopital's Rules

In general, we see that if we have a function y = f(x), and if this function has a derivative at x = a, we can sketch the picture below to depict the point and attention line. When x = a, y = f(a) so the tangent line will go through the point (a, f(a)). The derivative of the function at x = a is f'(a), so slope of the graph at that point is f'(a).

It follows that if (x, y) is a point on the tangent line, the slope between (a, f(a)) and (x,y) is (y - f(a)) / (x-a).

It follows that if (x, y) is a point on the tangent line, the slope between (a, f(a)) and (x,y) is (y - f(a)) / (x-a). This therefore have the slope = slope equation (y - f(a)) / (x - a) = f'(a), which we saw for y to obtain

y = f(a) + f'(a) * (x-a).

Since a, f(a) and f'(a) are just numbers, y as given above is a linear function of x. Of course it is no surprise to the tangent line has a linear graph, considering how we obtained it from a point and a slope.

This equation tells us that if we know the value of a function and its derivative at a point a, we can determine its approximate value at x by adding to the original value f(a) at a the approximate change `dy in y, as calculated by multiplying the change (x-a) in x by the slope f'(a) to get the rise `dy.

For any decently behaved function, this approximation will be good near x = a. For most functions the actual graph will at first gradually then more and more quickly curve away from this linear approximation.

This tangent-line approximation is therefore also called a local linearization of the original function. The word 'local' is applied because the approximation is most valid near the point, or in the locality of the point.

Local Linearization and Limits: l'Hopital's Rule

We can apply the local linearization to obtain limits in situations where we could not otherwise obtain them. Consider for example the limit shown in the figure below. If x = 0, using what we presently know about limits we end up trying to take the limit of the meaningless term 0 / 0. If, however, we look at the local linearizations of the numerator and denominator functions, we can easily save what happens to (e^(3x) - 1) / x as x -> 0.

We easily find that the equation of the tangent line to the numerator function is simply y = 3x, as indicated in the first graph in the figure below.

Since the denominator function y = x is already linear, we therefore see that as x gets closer in closer to zero and the numerator function gets closer in closer to the y = 3x function, the ratio of the numerator to denominator function becomes closer in closer to 3x / x = 3. We can therefore say that near x = 0, e^(3x - 1) / x is close to 3x / x which is close to 3, and that the closer we get to 0 closer these approximation will be. It therefore follows that the limit of the original expression is 3.

We can generalize these observations. Whenever we have functions f(x) and g(x), both of which take value 0 and some point a, we realized we cannot take the limit as x -> a by simply dividing the limits, since this would give us 0/0. However, if the functions have derivatives near the point x = a, we can imagine the limit as if the functions approach along the tangent lines. In this case the ratio of the values of the functions will be approximately equal to the ratio f'(x) / g'(x) of the slopes, with the quality getting stronger and stronger as x approaches a. In the limit, then, we will be able to calculate the limit of a quotient of the two functions by calculating the limit of the quotient of the derivatives.

We use this rule to find the limit of the expression sin^3(x) / 2x as x -> 0. The formal statement of l'Hopital's rule requires that f(0) and g(0) both be 0, and that the derivative g'(0) be nonzero. As shown below, the derivative functions f(x) and g(x) satisfy these conditions, with f(0) = sin^3(0) = 0^3 = 0, g(0) = 2 * 0 = 0 and g'(0) = 2. We can therefore say that the limit of the ratio sin^3(x) / (2x) this equal to the limit of the ratio 3 cos(x) sin^2(x) / 2, which is 0 / 2 = 0.

In the figure below we see that the functions y = 2x and y = sin^3(x) approach x = 0 in such away that the second function 'flattens out', while the first function maintains a constant slope, so while the values of both functions both approach 0, their ratio keeps changing, with the value of sin^3(x) becoming smaller and smaller compared to that of 2x. This behavior is reflected in the behavior of their local linearizations, shown in the 'magnified' box below.

We can also apply l'Hopital's rule to functions whose values become infinite as x -> infinity. This is the case for the ratio of the functions y = e^x and y = x. The condition here is that both functions have infinite limits as x approaches infinity.

The limit of the derivatives is the limit of the ratio of (e^x)' = e^x and x' = 1; in this form it is very clear that the numerator function approaches infinity for the denominator function remains constant, so that the limit must be infinity.

The same approach could be used to obtain the limit as x approaches infinity of, say, e^x / x^10. While it is fairly obvious from the graphs of y = e^x and y = x that the former function grows faster and faster while the latter grows at a constant rate, so that the result of the previous problem is fairly obvious, in this case the graph of x^10 also grows faster and faster and in fact, between x = 1 and x = 2, the graph of x ^ 10 overtakes that of e^x and appears to grow faster.

We could, however, note that the quotient of the derivatives is e^x / (10 x^9), which again satisfies the conditions of l'Hopital's rule so the weekend take the limit of the derivatives of these functions, obtaining e^x / (10 * 9 * x^8). It should be clear that this process will continue until we finally have e^x / (10 * 9 * 8 * 7 * ... * 1). Now we have a numerator expression would still approaches infinity while the denominator expression is a constant number -- a pretty large constant number, but still constant so that eventually e^x will exceeded by as much as we might wish. It now becomes clear that the limit of the original expression is infinite, and that e^x eventually exceeds x^10 by as much as we might wish.

"