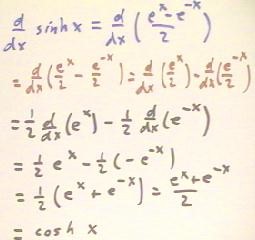

As shown below, the derivative of the hyperbolic sine can be shown to be equal to the hyperbolic cosine function. However, each step needs careful justification. There is a tendency among many students to write down the first line and the last line of the figure below with none of the lines in between. In going from the first line to the last, we apply the distributive Law of multiplication (in this case multiplication by 1/2) over addition, then we apply the property of the derivative of the sum or difference of two functions, the fact that the derivative of a constant times the function is equal to the constant times the derivative of the function, the derivative of e^x and e^-x, and some simple algebra. All the steps need to be shown in order to convince the reader (or the instructor) that you know what you are doing.

The derivative of ln( cosh(1+`theta)) is easily enough found as the derivative of a composite function f(g(`theta)), with f(z) = ln(z) and g(`theta) = cosh (1+`theta). This last function is of course a composite, but since the derivative of the 'inner' function 1 + `theta is 1, we proceed as below.

The function y = T / W cosh (W x / T) takes values y = T / W at x = 0, and y = T / W cosh(1) at x = -T / W and x = T / W.

The sag of a change his shape is given by this function will therefore be T / W cosh(1) - T / W, as indicated in the graph below.

As shown in the figure below, the sag is T / W ( cosh 1 - 1 ).

Attempting to verify this formula for the shape of a chain, we obtained the following data. However, it should be noted that the tension T was not observed at the appropriate point on the chain and should have been much less.

When substituted into the formula for the sag, instead of getting a good confirmation we obtained an absurd result. This could be because our measurements were made in the wrong units; units were not specified in the text, and time did not permit the derivation and validation of the equation. Even one a more nearly correct value for the tension was substituted, the results were absurd.

We verify that the function given satisfies the differential equation d^2 y / dx^2 = W / T `sqrt( 1 + (dy / dx)^2 ) by plugging it into the equation. We first calculate the first derivative then the second derivative of y with respect to x, as shown below. We plug the second derivative expression for d^2 y / dx^2 on the left-hand side of original equation, and the first derivative on the right-hand side, as indicated by the red arrows.

The result is a shown at the bottom of the figure. Note that the expression under the square root sign will be cosh^2(W x / T), and that the quality of the two sides follows very simply in another step or two.

First we prove that y = 1 must be a least upper bound for y values on this interval. We first note that y = 1 is in upper bound on this interval, since it if x < 1, then y = x < 1. Since there is an upper bound, there must be a least upper bound (if you don't remember which result, hypothesis or axiom tells us this, then you should re-read previous 'focus on theory' sections until you understand the status of this statement).

We now begin our study of differentiability. We begin with the idea of a global maximum on an interval. As a preliminary to outlining the proof of a very important result involving global maximum on closed intervals, we consider the function f(x) = x on an interval 0 < = x < 1. We ask whether the global maximum for the function on this interval exists within the interval.

First we prove that y = 1 must be a least upper bound for y values on this interval. We first note that y = 1 is in upper bound on this interval, since it if x < 1, then y = x < 1. Since there is an upper bound, there must be a least upper bound (if you don't remember which result, hypothesis or axiom tells us this, then you should re-read previous 'focus on theory' sections until you understand the status of this statement).

Now to show that y = 1 is the least upper bound, we assume that some number less than 1 is the least upper bound. Call the least upper bound M. By our assumption M < 1. But this simply cannot be, because for any number M < 1 there are numbers between M and 1. We can see from the definition of our function that all these numbers are > M, but since they are <1 they appear as y values for our function. This will show us that there is known number M < 1 that we can use for a least upper bound.

More formally we will say that since lim [x -> 1] (y) = lim [x -> 1] (x), then for any `epsilon there exists a `delta such that whenever | 1 - x | < `delta we necessarily have | 1 - y | < `epsilon. Now we let `epsilon = 1 - M. Since M is an upper bound for all y in our interval, then we always have | 1 - y | > = | 1 - M | = `epsilon. and we can never have | 1 - y | < `epsilon. This contradicts our assumption that the least upper bound is <1.

We therefore conclude that the least upper bound on this interval is 1.

However, y = 1 does not take place in the interval, it takes place at x = 1, which is an endpoint of the interval but is not included in the interval.

We therefore conclude that the least upper bound on this interval is 1.

However, y = 1 does not take place in the interval, it takes place at x = 1, which is an endpoint of the interval but is not included in the interval. As a result the global maximum for the interval doesn't occur on the interval.

Informally, we can say that for any x on the interval the global maximum can't occur there, because there is always another x value which is larger, and the function will be greater at this larger x value.

This result is not important, but the techniques we used in proving it are.

We use these techniques to outline the proof of the theorem stated below, that if f is continuous on a closed interval [ a, b ], then f has a global maximum on that interval. The important thing here is that the interval is closed (that is, that it contains its endpoints). We saw above that if the interval is open, we cannot make this claim, as we saw in the example above.

We begin by observing that our function if our function has an upper bound in the interval, it must have a least upper bound on the interval. We call this least upper bound M.

Now if we cut the interval in half, M must be the least upper bound for at least one of the halves. Otherwise each half would have a least upper bound < M, and the larger of these would be a least upper bound for the entire interval, contradict in the assumption that M is the least upper bound for the entire interval.

If we now cut the interval for which M is the least upper bound in half again, by a similar argument M must be the least upper bound on this half. So we can repeat the argument again for this half of the smaller interval, and we can continue repeating the argument as long as we wish, containing smaller and smaller intervals each of which is contained inside all the preceding intervals and each if which has M as its least upper bound.

These successively halved intervals each have M as least upper bound. By the Nested Interval Theorem, there is a number c common to all the intervals. The value of the function f at this number c must of course be less than or equal to the least upper bound M. However, an `epsilon-`delta argument given in your text shows that f(c) can't be < M, since if it was the least upper bound would have to be < M, which it cannot be because the least upper bound is M.

Since therefore f(c) = M, and since c is in the interval [a,b], the l.u.b. does in fact occur in the interval. This proves our theorem.

We now outline a proof of a result we have been using for quite awhile now. We wish to prove that if f has a local maximum at x = a, and if f is differentiable at a, then f'(a) = 0.

If f is differentiable at a, then the difference quotient has left-hand and right-hand limits at a.

Since f(a) is a maximum value, f(a-h) and f(a+h) must both be less than or equal to f(a). So the numerator of the left-hand limit must be negative or zero while that of the right-hand limit must be positive or zero, and the limits must be respectively < = 0 and > = 0.

Since the limits must be the same, it follows that they must both the zero.

You should read the rest of the assigned section and assure you understand the statements of the theorems in the section. The discussion of these results will continue next time, along with the first half of our review.

"