Quiz Problem

Today's quiz problem was to determine the difference between the left-hand and right-hand Riemann sums for the function y = e^x on the interval from x = 5 to x = 6, first for 10 subdivisions then for 100 subdivisions of the interval.

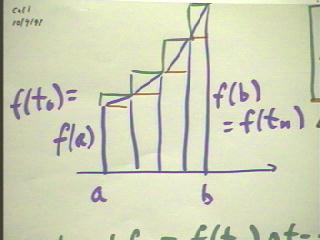

We begin by recalling that the left-hand sum of an increasing function is the sum of the areas under the red segments in the figure below. If the interval runs from t = a to t = b, then we can subdivide the interval into n segments using t0 = a, tn = b, and t1, t2, . . . , t(n-1) equally spaced between these values.

The left-hand and right-hand sums both contain intervals based on the function values f(t1), f(t2), . . . , f(t(n-1)), so as we have seen the areas of these intervals cancel out on subtraction. The only areas that don't cancel out are the last area f(tn) * `dt of the right-hand sum and the first area f(t0) * `dt of the left-hand sum, so the difference in the areas is f(tn) * `dt - f(t0) * `dt. Using the fact that t0 = a and tn = b, and factoring, we see that the difference must be ( f(b) - f(a) ) * `dt.

For the function f(x) = e^x between x = 5 and x = 6, we are using x instead of t for the independent variable, but the result still holds with the obvious modifications. We have a = 5 and b = 6, so the difference is going to the ( f(6) - f(5) ) * `dt = (e^6 - e^5) * `dt.

We can easily evaluate e^6 - e^5; we obtained approximately 250. The difference between the left-hand and right-hand sides is therefore approximately 250 * `dt.

If we subdivide the interval from 5 to 6 into 10 equal parts, we will clearly have `dt = .1, so that the difference is 250 * `1 = 25.

If the interval is subdivided into 100 equal parts, `dt = .01, and the difference is therefore 250 * .01 = 2.5.

If we look again at the graph below, we see that in general that for an increasing function the difference between the left-hand sum and the right-hand sum is represented by the sum of the areas of all the 'red-green rectangles' which live between the left and right altitudes of the various rectangles. It should be clear that if these rectangles were all slid to the right, they would stack precisely on top of one another and form a larger rectangle extending from the lowest left-hand altitude, corresponding to the function value f(a) at the left endpoint of the interval, to the highest right-hand altitude, corresponding to the function value f(b) at the right endpoint of the interval. The rectangle will therefore have altitude f(b) - f(a). Since its width is `dt, its area is ( f(b) - f(a) ) * `dt. We therefore see by simple geometric reasoning that the total area of all the 'error rectangles' agrees with the expression we obtained earlier for the difference between the left-hand and right-hand sums.

Text Problems

One situation encountered in the text involved a car for which the velocity vs. clock time graph was given. An approximation of the graph given in the text is shown below. The t axis is marked off in increments of 1 hour, and the velocities are given in mph. The graph given in the text was superimposed on a square grid, which permits reasonably accurate estimates to be made of areas and function values. Each rectangle in the text has a width of 1/2 hour and in altitude of 10 mph, and therefore corresponding to a distance of 5 miles.

The ultimate task was to compare the position of the car at clock times from 0 to 8 hours with the position of a truck moving at a constant speed of 50 mph.

Before considering this comparison we begin by estimating the distance traveled by the car during each hour. These distances are indicated on the graph below by the areas under the curve corresponding to the different hours. Estimates are made by first estimating the areas of the corresponding trapezoids, then correcting for the shape of the curve in comparison with the shape of the straight-line approximations of the trapezoids.

For example, the velocity on the first interval appears to go from 0 to approximately 55 mph. The trapezoidal estimate of distance would use the average height, 27.5 mph, as the average velocity and the 1-hour width as the time interval, obtaining an estimated distance of 27.5 miles. However, the concavity of the curve keeps it a bit higher than the straight-line approximation of the trapezoid, so we raise our estimates slightly to 30 mph.

Similarly on the second interval we base our estimate on the estimated velocities 55 mph and 72 mph, obtaining a trapezoidal estimate of 63.5 miles, which because of the downward concavity we ran up to approximately 65 miles. Similar estimates are made on the remaining intervals. Note that these estimates have not been made with great care and could easily be improved upon.

We can now make a table of the positions of the car relative to the starting point at the end of each hour. After one hour the car will have moved 30 miles and will therefore be 30 miles from its starting point. It moves 65 miles during the next hour and therefore will be 95 miles from the starting point at the end of that hour. Adding the 70 mile distance traveled during the third hour and then the 62 mile estimated distance traveled during the fourth hour we obtain positions 165 miles and 227 miles from the starting point. Note that these positions correspond to the accumulated areas of the intervals.

We can easily make comparisons with the positions of the truck, which moves 50 miles during each hour and therefore has positions 50, 100, 150 and 200 miles from the starting point at the end of hours 1, 2, 3 and 4. A comparison of the truck's positions with those of the car shows that the truck is clearly ahead after the first hour, narrowly ahead after the second, and behind after the third in the fourth.

We can understand this by comparing the graphs of the car's velocities with those of the truck. In the figure below the car's velocities are represented by the blue curve and those of the truck by the green horizontal line.

From clock time t = 0 until the time when the two curves first intersect, near the one-hour mark, the truck is moving faster than the car so it is no surprise that after the first hour the truck is ahead of the car. The distance deficit of the car corresponds to the approximately triangular area above the blue curve and below the green straight line.

After the graphs intersect the car begins to exceed the speed of the truck. The car therefore makes up its distance deficit, until the area of the blue curve above the horizontal green line is equal to the area of the 'deficit triangle' which preceded the intersection point. The (very approximate) clock time when this occurs is indicated by the vertical dotted line -- think about where you would locate this line. Note that at this point, the total area under the green horizontal line is equal to the total area under the blue curve.

The car continues to accumulate extra distance, represented by additional area above the horizontal line, until the blue and green graphs again intersect. Then the truck begins to make up distance, until somewhere in the vicinity of the second vertical dotted line the total area under the rectangle is again equal to the total area under the blue curve. At this point to distances are equal. Beyond this point, the car's speed is already much less than that of the truck in continues to decrease. The blue graph accumulate area much more slowly than the green graph, and the truck pulls away from the car faster and faster.

The figure below shows a graph of total distance vs. clock time for both the truck and car. The blue dots represent the accumulated areas under the car's velocity graph. Note that this graph is steeper for those clock times for the car's velocity is greater, and less steep or the car's velocity is less. This is as it should be because the slope of this graph represents the velocity of the car. The red dotted line, which should be but is not quite straight, represents the position of the truck. We see that for the first couple of hours the truck's position is greater than that of the car, but that sometime after the end of the second hour the graphs intersect as the car passes the truck. This occurs at the point where the accumulated areas under the velocity graph are equal.

The car remains ahead of the truck until the next intersection point, corresponding to the next point at which the accumulated areas under the velocity graph are equal. After this the car's velocity continues to decrease while the truck's velocity remains constant; the slope of the car's position graph therefore decreases while that of the truck's position graph remains constant, and truck clearly stays ahead of the car, in fact pulling away at a greater and greater rate.

Average Value of a Function

If we graph a linear function f(t) between t = a and t = b, we obtain a trapezoid like the one below. The average value of the function between these two points is clearly the average ( f(b) + f(a) ) / 2 of its values at a and b.

The integral of the function between these points, represented by the area of the trapezoid, is equal to the product of the average altitude of the trapezoid and its width. The integral is therefore ( f(b) - f(a) ) / 2 * (b - a) = average value * width.

Thus we see that for a linear function between a and b, integral = ave. value * (b - a). By extension, the same can be said for any trapezoid and therefore for any trapezoidal approximation graph. Since the integral of the function is the limiting value of the area under the trapezoidal approximation graphs of that function, as the number of subdivisions approaches infinity, this statement about integral and average value extends to any function over any interval over which it is integrable.

It follows that the average value of the function can be found by dividing its integral by the width of the interval over which the integral was evaluated. This situation is depicted in the figure below.

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

We have already seen the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus within the context of the depth vs. clock time model. Recall that the derivative of the quadratic depth function was a linear rate of depth change function, and that by integrating the rate function over a time interval we obtained the corresponding change in depth over that interval. We thus took a derivative of a quantity to obtain the rate of change of that quantity, then integrated that rate of change over and interval of the independent variable to obtain the change in the original quantity. You should carefully review how this was done numerically four-hour depth vs. time data, then symbolically for the quadratic model of this data.

In general if F(x) represents some quantity that depends on an independent variable x, its derivative, which we here represent by f(x), represents the rate which that quantity changes. When we integrate f(x) between two values x = a and x = b of the independent variable, we obtain the change F(b) - F(a) in the original quantity.

This process is represented in symbols below. Again, f(x) represents the rate at which the quantity F(x) changes. The graph in the figure below can be taken to represent the rate of which the depth of water in the container changes between two clock times. The area under this graph, which corresponds to the integral, represents the product of the average rate of depth change in cm/sec and the time interval in sec. This product is the change in depth in cm.

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus is stated below. It says that if f(x) is the derivative of F(x), than the integral of f(x) between x = a hand x = b must be the difference F(b) - F(a).

Another way of saying this is that we can integrate f(x) over and interval as long as we confined an antiderivative function F(x), which we then need only evaluated at the endpoints of the interval.

As an example, consider the function r(t) = 2t - 3 which represents the rate of depth change in a certain container. This function is linear, so its integral between t = 2 and t = 5 is represented exactly by the area under a trapezoid whose altitudes are r(2) = 1 and r(5) = 7. The average altitude of this trapezoid is 4, which can be taken to represent an average rate of 4 cm/sec. The width of the trapezoid is 3, which can be taken to represent a 3-second time interval. The area of the trapezoid is the product of this average altitude in average width, which represents 4 cm/sec * 3 sec = 12 cm, the total change in the depth.

The area is also represented as the integral from 2 to 5 of the function (2t - 3), as indicated that the bottom of the figure.

In the figure below we evaluate this integral using the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. The integral is F(5) - F(2), where F(t) is any antiderivative of the rate function 2t - 3.

We have already seen how to calculate the antiderivative of a linear function (the antiderivative of mx + b is .5 mx^2 + bx + c, where c can be any constant number). The simplest antiderivative of 2t - 3 is t^2 - 3t, obtained by letting c = 0.

If we therefore let F(t) = t^2 - 3t, we see that F(5) - F(2) = 10 - (-2) = 12. This is consistent with the value obtained for this integral from the graph.

We note two things. First, if we had taken as are antiderivative the function F(t) = t^2 - 3t + 80, corresponding to c = 80, our result would have been no different (evaluate F(5) - F(2) for this function and see for yourself). The reason is that the 80 will appear unchanged in both F(5) and F(2), and will hence cancel out. The same will be true no matter what value of c we might choose to use.

The second thing we note is that, though we easily evaluated the integral of the linear function of this example by interpreting a trapezoid, and could equally easily have evaluated it has a simple product of average rate and time interval, we cannot do this for function switch are not linear. We can, however, apply the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus to function which is finite and continuous over the interval of integration. That is, we can find the precise area under any curve, and hence the quantity represented by that area, for any finite and continuous function for which we can find an antiderivative.

This is a really big, really important result. Our entire technological civilization would never have developed without this result.

"