Calculus II

Class Notes, 1/11/99

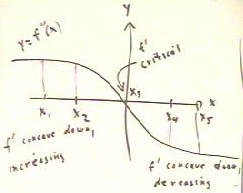

Graphing Antiderivatives

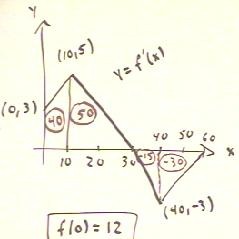

We find the function y = f(x) corresponding to the y

= f'(x) function depicted below, subject to the initial

condition that f(0) = 12.

- Recalling that the graph of y = f'(x) gives us the slopes of the y =

f(x) graph, we see that for the first interval from x = 0 to x = 10 this slope

is increasing and the graph of f(x) is therefore concave

upward, and with a positive slope due to the positive

value of f'(x).

- Over the next interval, from x = 2 and to x = 30, f(x) becomes concave

downward though maintaining a positive slope until x = 30, at

which point the slope will be zero.

- The slope then continues decreasing between x = 30 and x = 40, while

its slope remains negative over this interval. f(x) will

therefore be decreasing and concave downward over this

interval.

- Over the final interval, from x = 40 to x = 60, the slope increases

so that the graph becomes concave upward. The slope of

the graph however remains negative until x = 60, at which point the slope

will be zero.

By the Fundamental Theorem, which tells us that the change `df

over an interval is found by integrating f'(x) over

the interval, the changes in the value of f(x) are

represented by the areas under the graph of f'(x).

- These areas are easily found and are depicted in the figure

above.

From these areas we would conclude, as shown below,

that

- f(10) = f(0) + 40 = 12 + 40 = 52,

- f(30) = f(10) + 50 = 52 + 50 = 102,

- f(40) = f(30) + -15 = 102 - 15 = 87 and

- f(60) = f(40) + -30 = 87 - 30 = 57.

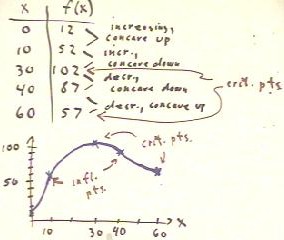

The figure below shows a table of values of f(x) vs. x,

with the behavior of f(x) indicated for each x interval.

- We note that (30, 102) and (60, 57) will be critical points, where

f'(x) = 0.

- We note also that at x = 10 and at x = 40, the slope

of f'(x) changed sign so that the concavity of

f(x) changed, indicating that these points are inflection points.

- The graph shown below corresponds to these behaviors.

The graph of a function y = f''(x) is depicted in the graph below.

From this graph of f'' we can determine the behavior of its antiderivative

f'(x).

- Since the values of f'' are decreasing for negative values

of x, it follows that f' will be concave

downward for negative x values.

- Since f'' is positive for negative values of x,

it follows that f' will be an increasing function for

negative x values.

- Since the values of f'' are increasing for positive values

of x, it follows that f' will be concave up for

positive x values.

- Since f'' is negative for positive values of x,

it follows that f' will be a decreasing function for

positive x values.

- Since f'' is 0 at x = 0, we conclude that f' has

a critical point at x = 0.

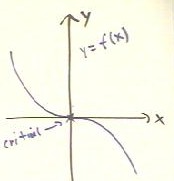

The graph of f'(x) is shown below, wth the specified value f'(0)

= 0.

We see that the graph of f' is increasing and concave downward

for negative x, reaching a critical point at x

= 0, and then decreasing and still concave downward for

positive x.

We now use the above graph of f' to determine the

behavior of the function f.

- Except for a critical point of f at x = 0, where f'(x)

= 0, we see that f'(x) is negative, so that f

will be decreasing.

- For negative values of x, f'(x) is increasing,

so f must be concave upward.

- For positive values of x, f'(x) is decreasing so

f must be concave downward.

The corresponding behavior of the graph of f(x) is shown below.

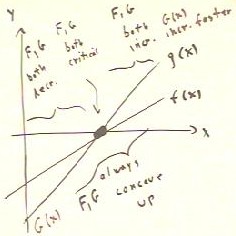

The figure below depicts the graphs of two functions f(x) and g(x),

which intersect one another at the x axis.

- We wish to find graphs of antiderivative functions F and G of f and g,

with F(0) = G(0) = 0.

- Since both the graphs of f(x) and g(x) are strictly

increasing, the graphs of their antiderivative functions F and G

will be always concave upward.

- To the left of the point where the two graphs meet,

both f and g are negative so the both the antiderivative

functions F and G will be decreasing.

- To the right of the point where the two graphs meet, both f and g are positive

so both the antiderivative functions F and G will be increasing.

- Both F and G will have critical values at the x value where f and g are

zero--i.e., at the intersection point.

- Since the magnitude of g(x) is always greater than

that of f(x), we see that g(x) will always have the steeper graph.

The figure below shows the corresponding behavior of the graphs

of F(x) and G(x).

- Both graphs start at the origin, since F(0) =

G(0) = 0.

- Both graphs begin with a negative slope and remain concave

upward.

- Since as we observed earlier the graph of G(x) is always steeper

than that of F(x), we see that G(x) immediately becomes less

that F(x) and, until the common critical point, G(x) continues

to decrease faster than F(x).

- To the right of the critical point, the steeper

graph of G(x) will increase faster than F(x),

so that G(x) will at some point overtake F(x).

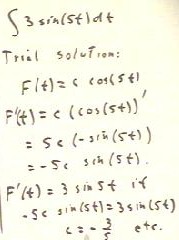

To find an antiderivative function of 3 sin(5t), which

we write as the integral in the first line below, we

recall that

- sine functions are obtained by taking the derivatives of

cosine functions

- the argument of the cosine function will be the same

as the argument of the derivative sine function (i.e., since the argument

of the sine function is 5t, the argument of the cosine function will also be 5t)

- there is such a thing as the chain rule.

We know that the derivative of cos(5t) is - 5

sin(5t).

- It would follow that the derivative of -1/5 cos(5t) is

equal to sin(5t).

- From this it follows that to get 3 sin(5t), we need to take the derivative

of 3 * (-1/5 cos(5t)).

We therefore conclude that an antiderivative of 3 sin(5t) is

-3/5 cos(5t).

Knowing that we get the derivatives of sines from cosine functions, we make an educated

guess that the antiderivative function will be some multiple

of cos(5t).

- We therefore set up a trial solution F(t) = c cos(5t), where

c is a constant to be determined.

- We easily see that the derivative of F(t) is F'(t) = - 5 c

sin(5t).

- Since we want the derivative to equal 3 sin(5t), we

set the two expressions for F'(t) equal, obtaining the equation

in the next-to-last line below.

- The equation is easily solved; we determine that c = -3/5.

- We then proceed to substitute this expression into the expression for F(t),

obtaining F(t) = -3/5 cos(5t) as before.

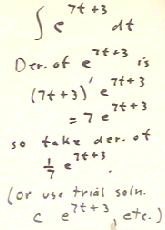

To find an antiderivative of e^(7t + 3), we observe

that the derivative of e^(7t + c) is 7 e^(7t + 3).

- We conclude that the function whose derivative is e^(7t

+ 3) is 1/7 e^(7t + 3).

We could also have used the trial function F(t) = c e^(7t + 3) in a

manner similar to that followed above.

We might try to find an antiderivative for e^(x^2).

We would probably be tempted to try a function of the form c

e^(x^2).

- The derivative of c e^(x^2) is 2x c e^(x^2).

- If we were to set this expression equal to e^(x^2),

we would find that c = 1 / (2x). This is not a constant

number, since x is a variable.

- We might decide to try using this value of c anyway,

especially if we have nothing better to try. But we aren't going to hold out a great hope

of success.

- It's a good thing we didn't hold out much hope of success, since by the product

rule the derivative of 1 / (2x) e^(x^2) has two

terms, only one of which is e^(x^2).

It turns out that there is no way to write an antiderivative of

e^(x^2) in algebraic form as a combination of familiar functions.

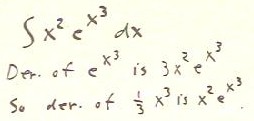

On the other hand, we can easily enough find an antiderivative of x^2

e^(x^3), as shown below.

- We see that the x^2 occurs as a result of the chain

rule.