We analyze a quadratic function y = a t^2 + b t + c by determining the locations of its zeros, if any, the location of its vertex, the points 1 unit to the right and left of the vertex, and the y intercept. We can find the value of y corresponding to a given value of t by substitution; we can fine the value(s) of t corresponding to a given y using the quadratic formula.

The first three of the four basic functions are y = x, y = x^2 and y = 2^x. We graph these functions by first making a table for each. We see that y = x yields a straight-line or linear graph, y = x^2 yields a parabolic graph with vertex at the origin, and y = 2^x yields a graph which is asymptotic to the negative x axis and which increases more and more rapidly for increasing values of x.

When a graph is stretched vertically by a given factor a, every point on the graph moves in the vertical direction until it is a time as far from the horizontal axis as it was before. If | a | is less than 1, every point moves closer to the horizontal axis and the graph appears to be compressed; if | a | is greater than 1, every point moves further from the horizontal axis and the graph appears stretched. If a < 0, then positive values of the basic function are transformed into negative values and negative values into positive, and the graph appears inverted. When the linear function y = x is vertically stretched by factor a the its slope is multiplied by a.

When a graph is shifted either horizontally or vertically, every point moves the corresponding horizontal or vertical distance, and the graph simply shifts left or right, or up or down, as the case may be.

When applying a series of stretches and shifts to a graph, we always apply the stretches first. Applying the shifts first would give a different result.

A variety of function families can be generated by applying one or more fixed transformations, and by also applying a transformation whose parameter varies over a given range.

A linear function is characterized by its slope and y intercept. It requires only a vertical stretch of the basic y = x function to match the slope of any desired linear function, and only a vertical shift to match the y intercept.

A quadratic function y = a t^2 + b t + c is characterized by the location of its vertex and by the value of a. It requires only three transformations to transform y = t^2 into a given quadratic. We first stretched the function vertically by factor a, then shift it horizontally and vertically to reposition the vertex.

A general exponential function y = A * 2^(kt) + c can be obtained from y = 2^t by a vertical stretch by factor A, a horizontal stretch by factor 1/k (or the horizontal compression by factor k), and a vertical shift c.

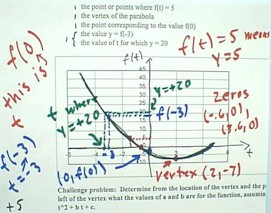

Given the graph of a quadratic

function, as shown below, we wish to indicate

The zeros are the points where the graph crosses the t axis.

The expression f(t) = 5 means that f(t), whose value is plotted on the vertical

axis, has the value 5.

The vertex of the parabola is the extreme point of the parabola and

lies on the axis of symmetry.

When we refer to f(0), we are talking about the value of f(t) when t = 0.

In the expression y = f(-3), we see that the -3 replaces t in the

expression y = f(t).

To find the t value of the function for which y = 20, we locate the y = 20 point on the

vertical axis and proceed straight across to the graph to the y = 20 point.

http://youtu.be/5h1HwFLQgKc

If we wish to find the values of a, b and c for the quadratic function y = a t^2 + b t + c, we note that the graph gives us the following information:

Our function is thus approximately y = 1 t^2 - 4 t - 3.

Before introducing the idea of basic function families, we review of couple of essential facts about exponents.

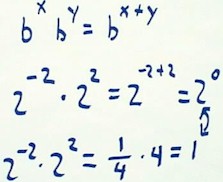

In the first place, b^x * b ^ y = b ^ (x + y).

- b^x means b multiplied by itself x times, and b^y means b multiplied by itself y times.

- So b^x * b^y will consist of b multiplied by itself a total of x + y times. Again, just common sense.

- People often make a mistake of thinking that 2 ^ 0 = 0, but this seemingly commonsense assumption actually violates common sense.

- This can easily be seen as follows:

2 ^ -2 = 1 / (2^2) = 1/4 (recall that raising a number to a negative exponent results in an inversion of sort e.g., 2 ^ -2 = 1 / (2^2) = 1/4).

So when we multiply 2 ^ -2 by 2 ^ 2 we get 1/4 * 4 = 1.

It follows that 2 ^ 0 = 1.

We could duplicate this argument for any number b, coming to the conclusion that b ^ 0 = 1 for any number b.

http://youtu.be/Xlhdi9i7rT8

We now introduce the first three of our four most basic function families.

- y = x,

- y = x^2 and

- y = 2 ^ x.

- the constant changes in y values for the y = x function,

- the symmetry of the y = equal x ^ 2 function, and

- the fact that the y = 2^x function doubles with every successive x value on the table.

http://youtu.be/da16stlP4k8

We sketch the graphs of these functions.

- The y = 2 ^ x function is called an exponential function; exponential functions all have the same basic shape, though some might be upside down and some inverted from left to right as compared to the function shown here.

- On one side or another an exponential function always approaches a horizontal line, coming closer and closer without limit but never quite reaching the line.

- This line is called a horizontal asymptote of the graph.

http://youtu.be/Fi46zzNiRfk Stretching and Shifting the Basic Functions

Starting with a basic function, we can think of stretching its graph either in the vertical or the horizontal direction, or both, then shifting the graph to the right or left (horizontally) or up or down (vertically).

If we consider what happens to a parabola when we stretch it vertically, we will gain valuable insight into how this process works.

We could also have stretched the y = x ^ 2 graph by a factor of 1/2, moving each point of the y = x ^ 2 graph to 1/2 its distance from the x axis.

We can even extend the idea of stretching to negative factors.

http://youtu.be/m5rV1nf7e9U

If we apply the same stretching idea to a linear graph, we see that stretching by a factor of 2, as it moves every point twice as far away from the x axis, has the effect of doubling the slope of the graph.

Suppose we wish to match the green dotted line (supposed to be straight but not quite looking that way), using just stretching and shifting transformations. How would we go about it?

- Note that we always apply stretching transformations before shifting transformations.

Then to match the green graph, we would have to raise the graph an estimated 6 units.

More generally, if we stretch the y = x graph by factor m, then raise it b units vertically, we obtain the graph of the general linear function y = mx + b.

We can see the variety of graphs possible for this general linear function by imagining that the parameter b is held fixed, which results in a fixed y intercept, while the parameter m is permitted to vary through all possible real numbers.

We might on the other hand wish to keep m constant and let b vary.

http://youtu.be/Df7h5dx92wc The Number of Transformations Required to obtain the General Function for each Basic Function

Any linear function can

be constructed by two geometric transformations: a vertical stretch and a vertical shift.

To obtain a given parabola by geometric transformations we must

usually employ three transformations, a vertical stretch to get the 'width' of the

parabola correct, then a horizontal and a vertical shift.

Another way of expressing the basic form of a quadratic function is y = a (x -

h) ^ 2 + k.

When we stretch and shift our basic exponential function y = 2 ^ x, we will think of a vertical stretch, a horizontal compression, and a vertical shift.

- The second of these forms reveals the vertical stretch A, the horizontal compression k and the vertical shift c.

Just as a we were able to fit a quadratic function to any three data points, we can fit an exponential function to any three data points.

http://youtu.be/ZalNjnaogKE