"

Class Notes Precalculus I, 9/29/98

Proportionality and Sugar Piles

Today's quiz problem was to determine a linear force vs. displacement function for a

pendulum, if it is known that a 5 in. displacement from a certain reference position

results in 3 pound resisting force, tending to pull the pendulum back to the reference

point, and also that a 9 in. displacement results of 7 pound resisting force.

- We then wish to use this function

to determine the force when the displacement is 15 in., and also the displacement when the

force is 13 pounds.

To solve the problem it is very helpful to sketch or graph of the force vs. the

displacement.

- The two known force-and-displacement pairs to give us two points on this graph.

- These points are (5 in., 3 lbs) and (9 in., 9 lbs); they are designated by (5, 3) and

(9, 7) on the graph below.

We can easily draw the graph of the linear function through these two points.

- The slope of this graph is the

slope between the points (5 lbs., 3 in.) and (9 lbs., 7in. ); this slope is 1 lb / in..

- If (x , y) is a point on this

graph, then the slope (y - 7) / (x - 9) must be equal to this slope and we have the slope

= slope form of the equation of the straight line: (y - 7) / (x - 3) = 1.

- This equation is easily solve for

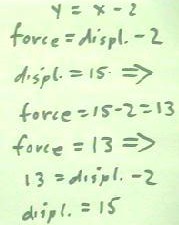

y to obtain y = x - 2.

Since y stands for the force, and x for the displacement, we can rewrite the equation y

= x - 2 in meaningful terms as

force = displacement - 2,

understanding that force will be in lbs. when the displacement is in inches.

Using this form of the equation it is easy to determine what to do define the force

when the displacement is 15 inches.

- Letting displacement = 15 we obtain

It is equally easy to determine what displacement corresponds to a force of 13.

(Coincidentally, this is the force we found above for the displacement 15. We will proceed

as if we didn't know this.)

- When we substitute 13 for the force we obtain the equation

- which we easily solve for the displacement.

- Of course we do obtain displacement = 15.

Video File #01

http://youtu.be/_PdqgIbnIl0

Video File #02

http://youtu.be/l6h2xa0OZRw

Video File #03

http://youtu.be/8F7VpPF3SRo

Sand Piles

We will use sand piles to illustrate some of the main ideas of

proportionality and to provide an introduction to power functions.

Actually are dealing with sugar piles here, but sand will behave in a similar way.

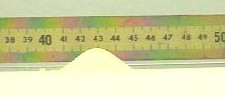

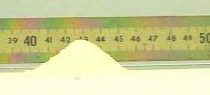

The first picture below shows a pile of sugar being formed by pouring a container full

of sugar in front of the 43-cm mark on a meter stick.

- The second picture shows the pile that results when the container has been emptied.

- We see that this pile forms an approximate cone with an approximately circular base.

- By reading the meter stick we see that the base appears to have a diameter of about 4.5

cm.

We pose following question: when the second container of sugar is added on top

of the first, will the diameter of the pile therefore double?

- If so, of course, we will end up

with a pile whose base has diameter 9 cm (double the 4.5 cm of the first).

- Before looking further, decide

whether you think this is the case.

- If not, decide whether the

diameter will more than double or less than double, and be sure that you explain your

reasoning to yourself.

- Then decide what you think will

happen in a third, then a fourth, then a fifth and finally a sixth container are poured on

the pile.

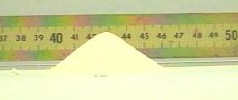

The pictures below show the result of pouring the second and the third container of

sugar onto the pile.

- When we doubled then tripled the amount of sugar in the pile, did the diameter

correspondingly double and triple?

It should be clear that the diameter did much less than double and triple.

- Rather than having a doubled

diameter of 9 cm, the second pile has a diameter of approximately 5.5 cm (you can probably

read the diameters to a greater accuracy than the figures that will be given here, and you

should do so).

The third pile appears to have a diameter of approximately 7 -- still not double the

diameter of the first, though the pile has three times as much sugar as the first.

The fourth and fifth piles have diameters that approach 8 cm, but they still do not

reach the double-the-first-diameter measurement of 9 cm.

Except for the last trial, where the sugar was poured carelessly and allowed to 'mound'

on the left half of the pile, all these piles seem to have approximately the same slope

along their sides.

- Another way seeing this is that each pile has the same ratio of height to diameter.

- The piles are reasonably close to being perfect cones, though their symmetry isn't

perfect and their tops are a bit rounded.

- To the extent that the piles form good cones with a consistent height-to-diameter ratio,

they are geometrically similar, with each one being a scaled-up version of the ones before

it.

If we imagine that the first sugar pile is made up of tiny cubes, and that each

subsequent pile is made up by 'inflating' each tiny cube by inflating it to form a larger

cube, then to increase the diameter from 4.5 cm to 5.5 cm would require that we increase

the length, width and height of each cube by 5.5 cm / 4.5 cm = 1.22 (approx.).

- Imagine that we were able to scale

up each cube to double its original dimensions.

- Then how many times the original

volume with the new sugar pile half?

- We might be tempted to say that it

would double.

- However, if we think a little bit,

we can see that just doubling the length of a cube, leaving its height and width

unchanged, will double its volume -- we would end up with the equivalent of two cubes laid

end-to-end.

- We would not have a cube with all

its dimensions doubled, since the width and height would not be less than the length; this

shape would not be a cube at all.

- To make this shape into a cube we

would have to first double its width, which would give us the equivalent of four cubes

laid down, as at four corners of a square.

- This figure would have four times

the volume of the first, but would still not be a cube until its altitude was doubled.

- This would of course require the

equivalent of four more small cubes, bringing our total to 8.

- It would therefore take the

equivalent of 8 small cubes to increase the original cube to twice its original volume.

- We can think of the process as

three subsequent doublings, each doubling the volume of the preceding figure.

- We 'stretch' the cube along its

length, obtaining twice the volume of the original.

- We then 'stretch' the resulting

figure along its width, doubling the volume of the previous figure and obtaining four

times the original volume.

- We finally 'stretch' this figure

in the vertical direction, doubling its height and thereby doubling the volume again,

obtaining eight times the original volume.

- By doubling the dimensions of each

tiny cube, we will therefore have increased the volume by 2 * 2 * 2, or 8, times.

- This is why doubling the amount of

sugar was not sufficient to double the diameter of the pile.

- To double the diameter, while

maintaining a geometrically similar shape, we would have to double width, length and

height.

- This would require 8 containers

full of sugar.

If we wish to increase the diameter by the factor 1.22 (remember, this is the diameter

ratio between the 1-container pile and the 2-container pile), we could imagine that we

take each tiny cube and increase its length by the factor 1.22, obtaining 1.22 times the

volume, then increase the width of the resulting figure by the same factor, obtaining 1.22

* 1.22 times the original volume, and finally increase the height by factor 1.22 to obtain

1.22 * 1.22 * 1.22 = 1.22 ^ 3 times the original volume.

- 1.22 ^3 = 1.8, which is nearly 2,

so the 1.22 factor is close to the factor that would double the volume. T

- The actual factor for doubling the

volume (take a calculator and check for yourself) is between 1.25 and 1.26.

- Since our diameters 4.5 cm and 5.5

cm are only approximate, it is very possible that the actual ratio is, between 1.25 and

1.26. It is also possible that the shape of the pile changed a little bit, so that the

second pile is not as nearly geometrically similar to the first as we might have thought,

and the tiny cubes would not have been stretched in such a way to give us perfect cubes.

A situation like this, in which we expect that one quantity, like the volume, changes

in proportion to the cube of another quantity, can be represented by the proportionality

equation y = k x^3.

- The number k represents a 'constant', a number which is the same no matter what the

values of y and x are.

- We will see that if we have a pair of x and y values, we can easily calculate k and

obtain a specific rule for determining values of y from values of x (or, with a little

simple algebra, determining values of x from values of y).

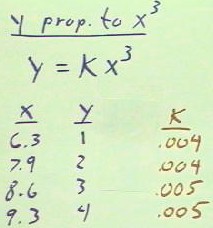

By making reasonably careful diameter measurements on a series of sugar piles made in

class, we obtain the y = volume vs. x = diameter data shown below.

- Diameters in class were not

measured in cm, so these data cannot be precisely compared to those in the pictures above.

We can test our hypothesis that the volume y should be proportional to the cube of the

diameter x by assuming that there is some constant k such that y = k x^3.

- We can then put different values of x and y into this proportionality and determine if k

is the same, or nearly the same, for all of our data points.

When we do this we obtain the k values shown in red.

- These values are not perfectly

constant, but they are fairly close to being constant.

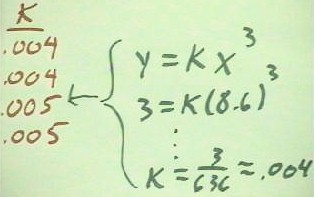

The calculation of one of the k values is shown below.

- (The right-hand part of the figure

has been cut off; the value of k, shown as approximately .004, is in fact .0048).

- The process is very

straightforward -- we just substitute x = 8.6 and y = 3, corresponding to the data point,

into y = k x^3 and solve for k.

Video File #04

http://youtu.be/F5aNoiBt3xQ

If we plot our data using DERIVE

and fit a cubic proportionality to our data (using FIT([x, kx^3], #1), we obtain y = .0046

x^3.

- Derive gives us a value of k very close to that determined above.

The curve fits the data reasonably well.

- However, it should be noted that a y = k x^4 fit works just about as well.

- With our small but significant inconsistency in the values of k, which in the above

table seem to increase from .004 to .005, this is not surprising.

In any case our results are not conclusive. We would have to repeat the experiment very

carefully, and measure all dimensions of each sugarpile to determine whether the shape of

the sugarpile does in fact change as it grows.

If careful measurements show that the shape remains constant, and if we measure the

diameter accurately, we should obtain a consistent value for k.

However, if geometric similarity is violated in any significant way, we will not have

this expectation.

Video File #05

http://youtu.be/s-X4d1zr7Uo

"