Class Notes Precalculus I, 10/13/98

Review Notes for Test

In response to a question raised by a student, we find the average slope

between the x = h and the x = k points of the graph of the general

quadratic function y = a x^2 + b x + c.

The figure below shows the situation.

- At x = h the y coordinate, or

'height', of the graph would be a h^2 + b h + c.

- Similarly at x = k the y

coordinate would be a k^2 + b k + c.

- The rise would therefore be be

- rise = a k^2 + b k + c -

(a h^2 + b h + c) = a (k^2 - h^2) + b (k-h).

- Since the run from x = h to x = k

is run = k-h, the slope is therefore

- slope = [ a (k^2 - h^2) +

b (k-h) ] / (k-h).

- If we factor k^2 - h^2, then

divide the denominator k-h into the numerator, we finally obtain a slope of

Figures to accompany numbered items on the Linked Outline

New items on the Linked Outline, covering material discussed since the last test, are

discussed below. See also the Linked Outline.

The slope = slope equation of the straight line between two given

points is obtained by setting the slope between the two points equal to

the slope between the one of the points and a general point (x,y).

- If the two given points are (x1, y1) and (x2, y2), then the slope between them is (y2 -

y1) / (x2 - x1).

- The slope between the first of the given points and the general point is (y - y1) /

(x-x1).

- Setting these slopes equal we obtain the equation

- slope = slope equation: (y - y1) / (x - x1) = (y2 - y1) / (x2 - x1).

- If we multiply both sides of this equation by (x-x1), then add y1 to both sides we will

obtain the slope-intercept form of the equation.

The figure below shows the points (x1, y1), (x2, y2) and (x, y), with the appropriate

slope triangles.

- In this example, rather than the

first given point, we find the slope to (x,y) from the second given point.

- The resulting equation (y - y2) /

(x - x2) = (y2 - y1) / (x2 - x1) is identical to the equation found in the preceding

paragraph.

- If we solve this equation for y

and simplify we will obtain the same thing as if we do the same to the equation of that

paragraph.

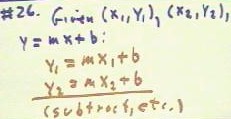

We can obtain the equation of the straight line give two points on its

graph by substituting the coordinates of each point into the linear form y = mx +

b.

- We obtain a system of

simultaneous equations.

- For example, if the points are

(x1, y1) and (x2, y2), we obtain the two equations y1 = m x1 + b and y2 = m x2 + b.

- It should be clear that when the

second equation is subtracted from the first, we eliminate b and obtain an equation we can

then solve for m.

- Having obtained m, we can

substitute it back into either of the equations and easily solve for b.

http://youtu.be/2iwrDiZsn2o

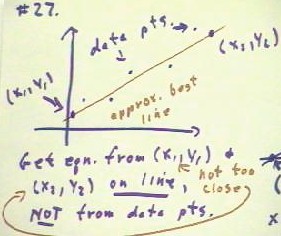

If we have a set of data which can reasonably be fit by a straight line,

we can find the approximate equation of the best fit line.

- We first sketch a straight line which comes as close as

possible, on the average, to the data points.

- We then find coordinates of two points on this straight line, not too

close together, and from these coordinates determine the approximate equation of

the line.

The actual best-fit linear function, which is the one given by DERIVE,

is the one whose graph minimizes the square root of the average of the deviations between

the function and the data point.

- In this course we will not concern

ourselves with techniques for finding this equation, but will simply think of the best-fit

linear function as the one which comes as close as possible, on the average, to the

points.

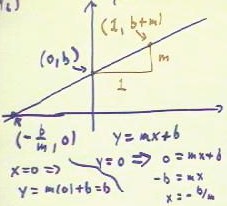

The basic points of the graph of the linear function y = mx + b are

taken to be the y intercept (0, b) (which is the point where x = 0), and

the point one unit to its right.

- Moving one unit to the right, the run is 1; since the slope is rise / run = m, it

follows that the rise must be m.

- Thus the y coordinate of the point will be b + m and, since the x coordinate is clearly

1, the point will be (1, b + m).

- We note that this point is higher than the y intercept when m is positive, and below the

y intercept when m is negative.

We note also that the x intercept of the function y = mx + b occurs when y = 0, and is

therefore found by solving 0 = mx + b for x.

- We obtain x = - b/m, so the

x intercept is the point (-b/m,0).

- The figure below shows these

points, and also shows the slope triangle used to find the point (1, b + m).

http://youtu.be/uMh1zWR-b6M

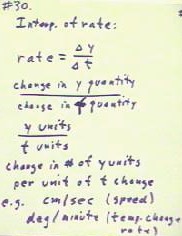

To interpret the average rate of change between two points on a graph,

we note that the rate is the change in the quantity represented by the dependent

variable (the rise) divided by the change in the quantity represented by the independent

variable (the run).

- When these quantities are divided

we obtain the number of units of change in the dependent variable per unit of change in

the independent variable.

- In our first flow model, for

example, we obtained the number of centimeters of depth change per second.

- A second is the unit of change of

the independent variable, and centimeters represent the units of change of the dependent

variable.

The difference equation a(n+1) = a(n) + c, a(0) = b, is evaluated for n = 0, 1,

2, 3, . . ..

- Starting with n = 0, we obtain a(1) = a(0) + c; since we know that a(0)

= b, we obtain a(1) = b + c.

- Continuing with n = 1, we obtain a(2) = a(1) + c; since we now know

that a(1) = b+c, we see that a(2) = (b+c) + c = b + 2c.

- Then n = 2 tells us that a(3) = a(2) + c; having found that a(2) = b +

2c we see that a(3) = b + 3c.

- The pattern that emerges is

a(1) = b+c,

a(2) = b + 2c,

a(3) = b + 3c,

. . . ,

a(n) = b + n * c.

It is clear that this

pattern is linear, changing by the same amount for each subsequent value of n.

http://youtu.be/Yujiy-vEMMo

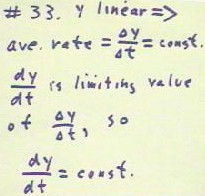

The average rate at which a function changes is given by `dy / `dx.

- This rate is represented by the average slope between two points of the

graph of the function.

- If the function is linear, then the slope is always the same, so we

have `dy / `dx = constant.

If we speak of the instantaneous rate which a function changes, we

mean the rate at which it changes at a point of its graph, as the run of a series of slope

triangles originating at that point shrinks down toward 0.

- We then no longer speak of the average slope or average rate, but the instantaneous

rate.

- This rate is designated dy / dx.

- It should be clear that for a linear function, this rate is again always the same, so we

right dy / dx = constant.

(The figure below should be labeled #32). These equations, `dy / `dx =

constant and dy / dx = constant, are called rate equations.

- The first is an average

rate equation and the second is an instantaneous rate equation.

- Rate equations (later called

differential equations) play an extremely important role in mathematics, since they allow

us to express the ways in which rate change, and since these equations can often be solved

to find important function models.

- Solving these equations requires

the use of calculus, and we will not solve them in this course.

- We will, however, look at how

to write certain important rate equations.

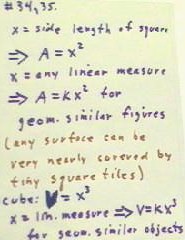

If the length of the side of the square is doubled, we obtain a square

large enough to contain 4 of the original squares (two rows of two

squares each). If the side of cube is doubled, we obtain a cube large enough to contain 8

of the original cubes (two layers each containing to rows of two cubes each).

- As the side x of a square is changed, its area is A = x^2. As the side x of a cube is

changed, its volume is V = x^3.

- If x is any linear dimension of a square, that is, any dimension that

can be measured by a ruler (such as its perimeter or its diagonal), then the area

of the square is A = k x^2, where k is a constant that depends on which linear

dimension is being measured.

- We say that the area of the square is then proportional to the square of the

linear dimension.

- If x is any linear dimension of cube, then the volume of the cube is V = k x^3,

were k is a constant which depends on which linear dimension is being measured. We say

that the volume of the cube is then proportional to the cube of the linear

dimension.

- If two objects are geometrically similar, then if x is any linear

dimension of the corresponding class of objects (e.g., the diameter of the circle, the

circumference of a sphere, the radius of the base of a cone whose height is equal to its

diameter), then

- The surface of the second

object can be 'tiled' as accurately as desired by tiny squares in exactly the

same way as the first, with the sides of the squares in the same proportion is the linear

dimensions of the two objects.

- Furthermore, the volume of

the second object can be filled as accurately as desired by tiny cubes in exactly

the same way of the first, with the sides of the cubes in the same proportion is linear

dimensions of the two objects.

- It follows that for any class of geometrically similar objects, area is

proportional to the square of a given linear dimension and volume is proportional to the

cube of this dimension.

- That is, area = k x^2 and

volume = k x^3.

http://youtu.be/JU3FzU8_GqE

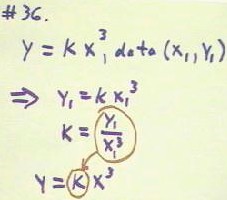

If we know that two quantities y and x are exactly related by proportionality y

= k x^p (e.g., A = k x^2 or V = k x^3), then one data point (x1,y1)

suffices to find the value of k.

- We merely plug in the values x1 and y1, obtaining y1 = k x1^p, and solve for k. (The

result is k = y1 / x1^p).

- If we then substitute this value of k into the form y = k x^p, we obtain a specific

function relating y to x.

If the proportionality y = k x^p is not exact, we can find a reasonably

good approximation to the best value of k by substituting every data point into

the form to obtain a value of k for that data point.

- We then average the values of k

for all the data points.

- (A better alternative is to use

DERIVE or another computer algebra system to find the best y = k x^p fit to the data).

The example below shows how to

find k for a y = k x^3 proportionality.

- x1 and y1 are to be regarded as

known numbers.

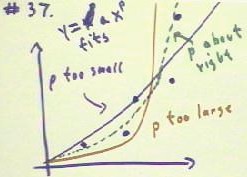

To determine the best y = k x^p proportionality for the data set by using DERIVE, we

use the syntax FIT([ x, k x^p], #1) for different values of p.

- Using the geometry of the

situation or other information to predict the best value of p, we try various values in

the neighborhood of the predicted best value until the graph of the resulting fit function

best matches the graph of our data.

- An optimal fit will lie close to

the curve and will give random residuals.

The figure below shows the data set, represented by large blue dots, and three

attempts to find the right value of p for a power-function fit.

- The red graph depicts a fit when

the value of p is too large, resulting in residuals that lie above the graph for small

values of x and below the graph for large values of x.

- The blue graph depicts a fit when

the value of p is too small, resulting in residuals that tend to be below the curve for

small values of x and above the curve for large values of x.

- The dotted green line depicts a

value of p for which the residuals seem to alternate randomly between being above and

below the graph; this function seems to have about the right value of p.

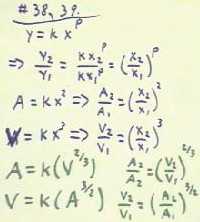

If y = k x^p, then

- y2 / y1 = (k x2^p) / (k x1^p) = (k/k)(x2^p / x1^p) = x2 ^ p / x1 ^ p = (x2 / x1) ^

p.

- This is shown in the figure below.

If y = k x^p, then

- x^p = y / k and x = (y/k) ^ (1/p) = (1/k)^(1/p) * y^(1/p).

- Since k is constant, (1/k) ^ (1/p) is also constant so we might as well call it k.

- This k has a different value than the k of y = k x^p, but it is still constant.

- We can thus say that the proportionality of x to y is x = k y^(1/p).

Since we have x = k y ^ (1/p), we have

- x2 / x1 = (k y2^(1/p)) / (k y1^(1/p)) = ... = (y2 / y1) ^ (1/p), where the intermediate

steps are identical to those used previously.

Thus, given the ratio of two x values we can obtain the ratio of the

corresponding two y values, and given the ratio to y values we can obtain the ratio of the

corresponding x values.

For most real objects the surface areas of geometrically similar objects are

proportional to the square of linear dimension, and volumes are proportional to the cube

of linear dimension.

- We could write this as area = kA x^2, and volume = kV x^3, where kA and kV are

understood to be different proportionality constants.

To get the proportionality of area to volume, we can solve the volume

proportionality for x, obtaining

- x = (volume / kV) ^ (1/3), and then substitute this into the area proportionality.

- We will obtain area = kA * [ (volume / kV) ^ (1/3) ] ^ 2 = kA * (volume / kV) ^ (2/3) =

(kA / kV^(2/3) ) * volume ^ (2/3).

- The expression (kA / kV ^ (2/3) ), which since kA and kV are constant must also be a

constant, can simply be called k, and we have the proportionality

- area = k (volume) ^ (2/3).

We can follow similar procedure, this time solving the area proportionality for x and

substituting into the volume proportionality, to obtain

- volume = k (area) ^ (3/2), where the value of k is different than in

the previous proportionality.

It will follow that for two geometrically similar figures, the ratio

areas for two given volumes will be

- area 2 / area1 = (volume2

/ volume1) ^ (2/3), while the proportionality of volumes for two given areas will

be

- volume2 / volume1 = (area2

/ area1) ^ (3/2).

These relationships are summarized in the figure above.

http://youtu.be/BFiQmZhDdhI