Consistency of the Three Experiments

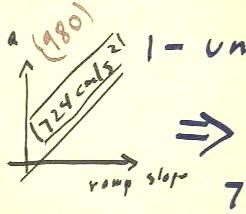

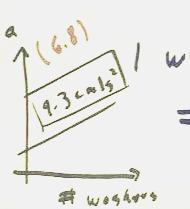

The two graphs shown below summarize results of an acceleration vs. ramp slope and then acceleration vs. number of washers experiment has conducted by different groups of students.

The slope of the acceleration vs. ramp slope graph is 724 cm / sec ^ 2, as compared with the accepted value of 980 cm/second ^ 2. This slope indicates that they ramp slope change of one unit will result in an acceleration change of 724 cm/second ^ 2; a change of .01 unit in the ramp slope would therefore change the acceleration by .01 of this amount, or 7.24 cm / sec^2.

The slope of the acceleration vs. number of washers graph is 9.3 cm / sec^2, indicating that each additional washer should increase the acceleration of the cart by 9.3 cm / s^2. The value obtained during the last class was 6.8 cm / sec^2 / washer, and this value shown in red in parentheses for comparison.

We wish to determine the slope change corresponding to the addition of a single washer. A one unit slope change results in an acceleration change of 724 cm / s^2; a 1 washer change in the accelerating force results in a much smaller acceleration change of 9.3 cm/second ^ 2. We easily determine that 9.3 cm / s^2 is .013 of 724 cm / s^2, and conclude that a 1-washer force (the force of gravity on one washer) is equivalent to a slope change of .013 for the cart used in the experiment.

A reasonably careful observation made in class, using the same cart, indicates that the effect of gravity on 5 washers (this number includes those required to overcome friction) will result in a constant velocity on a slope of .0067 while 10 washers resulted in a constant velocity on a slope of .040. The difference in slope corresponding to the addition of 5 washers was therefore approximately .033. This is a slope change of .0065 per washer. This calculation is represented graphically below.

This is not consistent with results obtained above, where we predicted that the addition of a washer would correspond to a slope change of .013.

This inconsistency is in part the result of our low value for the slope of the acceleration vs. slope graph, where we obtained 724 cm / s^2 instead of the accepted 980 cm/second^ 2. Noting that the slope of the acceleration vs. number of washers graph has also been measured as 6.8 cm / sec^2 / washer, in comparison with the 9.3 cm/second ^ 2 / washer used here, we could recalculate all results based on these values. All results would be much more consistent with the .033 slope difference observed.

Newton's Second Law

The graph below indicates the result of an acceleration vs. force experiment. We say 'acceleration vs. force' because the force was the independent variable over which we had control (e.g., when we added hanging washers), though we have graph force vs. acceleration as is more traditional. The reason for this orientation of the graph will become clear momentarily.

The red line on the graph represents the results of an actual experiment, in which we have not compensated for friction. We see that 0 acceleration corresponds to a nonzero force (since the graph intercepts the F axis for a positive force), and actual acceleration doesn't begin until this force is exceeded. The actual net force that results in the acceleration is in fact reduced by the amount of this frictional force. If we reduce the force at every point of the red graph by this amount, to compensate for friction and indicate the actual net accelerating force, we see that the graph will pass through the origin and that acceleration and force will therefore be proportional.

We write the proportionality as F = m a, where m is the slope of the graph. This slope will correspond to what we call mass. Mass is one of the four undefined units in physics, one of the four units in terms of which all other units are expressed. These four units are the unit of distance, the meter; the unit of time, the second; the unit of electric charge, the Coulomb (which will not encounter until second semester); and the unit of mass, which we called the kilogram (kg). A kilogram is very nearly the mass of 1 liter of water, though the international standard kg is a cylinder of durable metal residing, I believe, in Paris (your text will tell you more accurately than I will).

For an object with high mass, it takes a lot of force to give it even a moderate acceleration. This is indicated in the second graph below, where more force per unit of additional acceleration is required for the 'high mass' line than for the 'low mass' line.

We need to invent a unit for force. Our unit will be most convenient if 1 force unit has the effect of accelerating a single mass unit at a unit acceleration. Since the mass unit is the kg and the acceleration unit is the meter/second ^ 2, we want our force unit to accelerate 1 kg at 1 m/s^2. We can easily design an experiment to measure the force that has this effect. All we need is a 1 kg cart and a good sized pile of washers. Whenever number of washers of takes to give the cart and acceleration of 1 meter/second ^ 2 (compensated for friction, of course) will give us our unit force. That force is the force exerted by gravity on those washers.

We call this unit the Newton, in honor of Isaac Newton, who formulated the laws of motion. The proportionality F = m a these known as Newton's Second Law of Motion.

Let us apply Newton's Second Law of Motion to the situation depicted below, where a 10 kg object is subjected to a net force of 40 N (the net force is in this case thought of as the applied force less the resisting force of friction; so for example if there is a 5 N frictional force we would have to apply a 45 Newton force in order to achieve a 40 Newton net force). If the object begins at rest and accelerates through a displacement of 50 meters, we wished to determine its final velocity.

We already know the initial velocity v0 and the displacement `ds of the object. If we can find the value of a, vf or `dt, we can solve the motion problem. We have just seen that acceleration can be determine from force and mass, so we rearrange Newton's Second Law F = m a to obtain a = F / m and we plug in our given force and mass to obtain a = 40 N / 10 kg = 4 m/s^2 (we know that when force is given in Newton's and mass in kg the corresponding acceleration will be in meters/second^2; we will see soon how to manipulate the units formally, but for now we simply taken terms of the definition of the Newton).

We therefore know the values of the variables a, `ds and v0, and wish to find vf. The fourth basic equation of uniform accelerated motion, vf^2 = v0^2 + 2 a `ds, contains these four variables and can therefore easily be solve for vf. This solution is left to you.

If we generalize the situation by calling the net force F, the mass m and the displacement `ds, we see immediately that the acceleration is a = F / m. Then the equation vf^2 = v0^2 + 2 a `ds becomes vf^2 = v0^2 + 2 (F / m) `ds, as depicted in the figure below.

Recall that a uniform acceleration applied over a time interval `dt gives the same change in velocity for any initial velocity, while a uniform acceleration applied over the displacement `ds gives the same change in squared velocity for any initial velocity. This idea suggests that we might wish to solve the present equation for the product F `ds. Doing so we obtain the equation

F `ds = 1/2 m vf^2 - 1/2 m v0^2.

The product F `ds has the effect of increasing the quantity 1/2 m v^2, whatever the value of the initial velocity. We saw earlier in the context of washers, carts and ramps that the product F `ds of force and displacement seems to be related to what we understand as work, and that one possible product of work is an increase in what we might think of as the energy of motion. We make these intuitive ideas concrete with the following definitions:

Initial definition of work: When a force F is directed parallel to and in the same direction as a displacement `ds, the product F `ds is defined to be the work done by the force through the displacement.

Definition of kinetic energy: an object of mass m moving at velocity v has an energy of motion, or kinetic energy, equal to 1/2 m v^2.

The equation

F `ds = 1/2 m vf^2 - 1/2 m v0^2

therefore says that the work done by the net force on object is equal to the kinetic energy change experienced by the object.

This constitutes a first statement of what is called the Work-Energy Theorem. This statement will later be modified and amplified to include other kinds of forces and energy, but this statement if understood in the context of our experiences contains most of the essence of the full statement of the Theorem.

"