"

Class Notes Physics I, 11/09/98

Rotational Motion

http://youtu.be/iniXAUekOB0

http://youtu.be/Vip-PoLxiUc

http://youtu.be/IbDV0sOfJj8

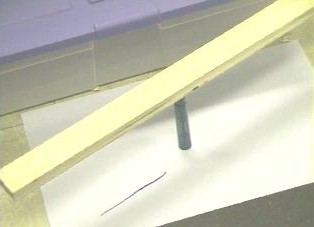

A beam consists of a rectangular piece of plywood approximately 60 cm long, 5 cm wide

and 3/4" (approx. 2 cm) thick. Its mass is approximately 300 grams.

- In the picture below we see the beam balanced on the flat tip of the cap of a Mr. Sketch

marker.

- These markers are good for this experiment because the top of the cap forms a flat

circular surface with a radius of approximately 2 mm (they are good for their intended

purposes also, and smell really good).

- They thus provide a low-friction surface on which a beam of this type can be (somewhat

precariously) balanced and rotated about the balancing point.

The system will in fact be rotated by means of a mass suspended by a thread over a

pulley. The details are in the video file for distance students; in-class students have

experienced the situation and will understand the setup.

The line on the paper shows the initial orientation of the beam. It can be drawn by

positioning a straightedge parallel to the beam.

A second line is added to indicate the position at which the weight suspended over the

pulley strikes the floor, with result that the external force on the system is essentially

eliminated. If the beam is permitted to continue rotating until friction brings it to

rest, a third line can be added to indicate this position.

The first part of the experiment consists of timing the system as it accelerates from

rest to the point where the weight strikes the floor, then as it comes to rest.

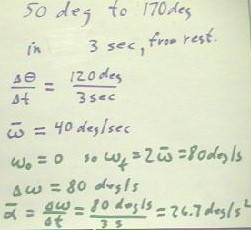

The quiz problem preliminary to this experiment asked for the average velocity, in

degrees/second, for a system whose angle with the positive x axis changes from 50 degrees,

at which point the system is that rest, to 170 degrees.

- The problem also asks for the acceleration of the system, in degrees/second/second,

assuming a uniform acceleration.

We easily reason this problem out by analogy with what we have done for motion along a

straight line.

- Our 'distance' from 50 degrees to 170 degrees is clearly 120 degrees

- Traveling 120 degrees in three seconds gives us in average 'velocity' of 40

degrees/second.

- If acceleration is uniform, then since the initial velocity is 0 degrees/second the

final velocity must be 80 degrees/second.

- The change in velocity will therefore be 80 degrees/second, and the 'acceleration' must

therefore be (80 deg / sec) / (3 sec) = 27 deg/sec (approximately).

We might be bothered by the fact that we never measured distance in degrees before, or

velocity in degrees per second, or acceleration in degrees/second^2.

- In fact we are not really measuring velocity at all, at least as we have conceived it

before.

- If an object rotates, it is very likely that different parts of the object rotate at

different speeds, as measured in meters/second (that is, the parts closer to the axis of

rotation move more slowly than parts further from the axis of rotation).

- Still, our reasoning in this problem seems to make a great deal of sense.

When we are talking about 'velocity of rotation', where we naturally measure position

in things like degrees, radians or revolutions, we see that we are measuring position by

angles.

- We therefore speak of angular position, angular velocity, and angular acceleration.

- Rather than using s for position and `ds for change in position, we use the Greek letter

`theta for angular position and `d`theta for change in angular position.

- Rather than using v for velocity we use `omega for angular velocity, and rather than

using a for acceleration we use `alpha for angular acceleration.

The figure below shows the reasoning in this situation, using the angular quantities

`d`theta, `omega and `alpha to represent angular displacement, angular velocity and

angular acceleration.

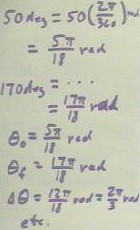

We note that we could have expressed our angles in radians.

- Since 2 `pi radians measures the

same angular displacement as 360 degrees, we can convert 50 degrees and 170 degrees to

radians, as shown below.

- Our original and final angular

positions are `theta0 = 5 `pi / 18 rad and 17 `pi / 18 rad, so our angular displacement is

- `d`theta = `thetaf - `theta0 = 12

`pi / 18 rad = 2 `pi / 3 rad.

- We could then proceed to find the

average angular velocity as `d`theta / `dt, then we could reason out the final velocity,

change in velocity and angular acceleration in the usual manner.

- We would obtain average angular

velocity 2 `pi / 9 rad / sec and angular acceleration 4 `pi / 27 rad/sec/sec; you should

verify these possibly erroneous results.

http://youtu.be/0AXbjW7WvE4

It might not be clear to you why

we use radians, which carry along that `pi, often involve unpleasant fractions, and are

harder to visualize than degrees.

- The advantage to radians is that on a circle of radius r, the arc distance corresponding

to angular displacement `d`theta will be `ds = r * `d`theta

- This is a very simple calculation, especially when compared to what we have to do if the

angle is in degrees.

- Angular velocities and angular accelerations are similarly related in a very simple

matter to the velocities and accelerations of points at a distance r from the axis of

rotation.

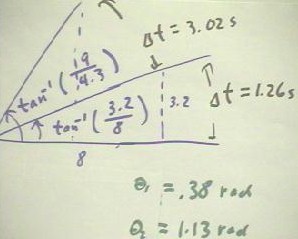

The figure below depicts data taken in an experiment in which a single 3-gram washer

was suspended over a pulley by a thread, with the other end of the thread attached to a

free end of the beam.

- The rays depict the original angular position of the beam, the position of the beam when

the washer hit the table, and the final position of the beam.

- Time intervals between successive

positions are indicated.

Angles were determined by using the original direction as the x axis, then constructing

right triangles and measuring x and y coordinates.

- The indicated angles were approximately .38 rad and 1.13 rad.

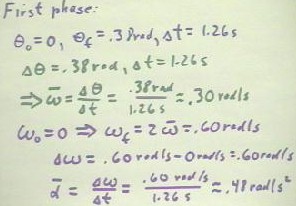

The first phase of motion, from rest to the position where the external force ceased,

is characterized by an initial angular position of 0, a final angular position of.38

radians, and time interval of 1.26 seconds.

- We easily determine that the average angular acceleration for this phase must be.48

radians/second/second, with a final angular velocity of .60 radians per second.

http://youtu.be/K6JX-eHhSN4

We can analyze the second phase of motion into ways.

- Our first analysis uses the obvious fact that the final velocity of the first phase is

equal to the initial velocity of the second phase, and assumes the results of the analysis

of the first phase of motion.

- Thus we would have for the second phase an initial angular velocity .60 radians/second,

final angular velocity 0 (the second phase ends when the beam comes to rest), and a time

interval of 3.02 seconds.

- We conclude that change in angular velocity is -.30 rad/s and that angular acceleration

is -.2 rad/s^2.

An alternative analysis considers the initial angular velocity to be unknown.

- Knowing the final angular velocity and time interval, we can determine the original

angular velocity from our implicit knowledge of the angular displacement.

- The angular displacement is from .38 radians to 1.13 radians, or `d`theta = .75 rad.

- From this angular displacement and the time interval we determine that the average

angular velocity is .25 radians/second.

- Following the usual line of reasoning, we see that the change in angular velocity must

therefore be -.5 rad / sec (in this situation is the final, not the initial angular

velocity that is 0, so the change in angular velocity must be negative, and must have

magnitude double that of the average angular velocity).

- We therefore obtain an average angular acceleration of -.17 radians/second^2.

- The velocity change in 3.02 sec would therefore be approximately -.5 rad/sec.

The results obtained are reasonably consistent.

- The second analysis gives us an initial angular velocity of .5 radians/second, as

opposed to the .6 radians/second final angular velocity of the first phase.

- The two quantities must of course in reality be equal, and the difference in the results

obtained from the data might well be explained by errors in timing.

- Our angular accelerations for the second phase are also reasonably close.

- This provides reasonable confirmation of the assumption of uniform angular acceleration

on which our results were based.

http://youtu.be/YsUqLxkvC3U

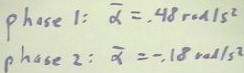

Our final result is that under the influence of the washer the average angular

acceleration of the system seems to have been approximately .48 radians/second^2, while

under the influence of only friction the average angular acceleration is approximately

-.18 or -.19 radians/second^2.

We therefore see that, as expected, the acceleration due to the frictional force is

approximately 1/3 that resulting from the force of gravity on a three-gram washer, when

that force is applied at the end of the beam.

http://youtu.be/t5cylz6v-2U

"