The quiz was to determine the forces acting on a ladder 10 feet long, leaning against a frictionless wall with its base 6 feet from the wall. It is assumed that the coefficient of friction on the floor is sufficient to keep the ladder and equilibrium, and that the mass of the ladder is uniformly distributed over its length

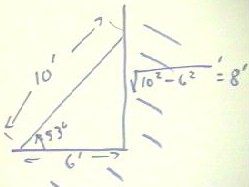

Preliminary to analyzing the forces, we work out the geometry of the problem.

We know that the weight of the ladder can be considered to act at its center of mass, which by the uniformity of the mass distribution will be at the center of the ladder. This is indicated by the purple weight vector in the figure below.

Since only two forces act in the vertical direction, they must have equal magnitudes and opposite directions so we observe that | Nfb | = | W |.

We can find the force Nwb by considering the condition of rotational equilibrium about the lower end of the ladder.

We use the three conditions of equilibrium to determine the forces:

Statics and Dynamics of a Pendulum

We begin by looking at the forces acting on a pendulum consisting of a mass m and a length of light string, suspended from some sort of fixed support. The distance from the fixed point of the string to the center of the mass is designated L.

In the figure below the dotted line represents a vertical line, along which the pendulum would hang if it was in equilibrium. We assume that the pendulum is displaced a distance x from its equilibrium position.

- It is in fact clear that the net force on the system will have a component to the left, which will accelerate the pendulum mass to the left (there might also be a vertical component to the net force; we will shortly make an assumption by which this force can be ignored).

Now, if the angle of the pendulum with vertical is small, practically all of its displacement back to the equilibrium position will be in the x direction.

If the pendulum is in y equilibrium, then the y component of the tension is equal to the weight W.

We now have the situation depicted in the figure below, where to a good approximation T = W.

- For small displacements, therefore, Tx / T = x / L.

- This is equivalent to saying that Tx = m g ( x / L ).

The situation is now as depicted in the figure below, for the net force Tx, approximately equal to m g ( x / L), acts to restore the pendulum to its equilibrium position.

Now, since a small displacement x results in a net force of magnitude Tx, we see that the acceleration of the pendulum back toward its equilibrium position must be a = F / m = -Tx / m = - m g (x / L) / m = - g ( x / L ). (The - sign indicates that the direction of the acceleration is opposite to the direction of the displacement x; this must be the case since, for example, a positive displacement x results in a force F in the negative direction, back toward equilibrium).

We have thus obtained an expression for the acceleration a has a function of the displacement x from equilibrium: a(x) = - g ( x / L ).

We now use a little bit of calculus to see the connection between this force model and the observed behavior of the pendulum, particularly the 2.65 rad / sec angular velocity that seems to model its motion.

We know that average acceleration is aAve = `dv / `dt and that average velocity is vAve = `dx / `dt. In calculus we take the limiting values of these average quantities, as `dt -> 0, and we obtain instantaneous acceleration and velocity. We denote these quantities a = dv / dt and v = dx / dt.

(The next couple of steps involve calculus and can be ignored by non-calculus students.)

From the above observations it follows that a = d (dx / dt) / dt, which we write as a = d^2 x / dt^2.

Since the force picture gave us the knowledge that a = - g ( x / L ), we conclude that d^2 x / dt^2 = - ( g / L ) x.

Calculus students will verify that this equation can be solved by the function x(t) = A cos( `sqrt( g/L) * t). That is, if this function is substituted into the equation, and both sides are simplified, we end up with an identity.

Simple Harmonic Motion

In the situation we have just analyzed, we have a force Tx = - (m g / L) * x which tends to pull the mass m back toward its equilibrium position.

This situation is very similar to the situation we modeled using a rubber band, where a force which we modeled by F = - k x pulled some object back toward the equilibrium position where the rubber band was at its unstretched length. Recall some of the results we obtained for that situation, in particular the one that said that the potential energy of the system at position x was 1/2 k x^2.

In fact, for small displacements x the pendulum obeys the same F = - k x law. F is just the restoring force Tx, and k is the quantity m g / L. (If in the expression F = - k x we substitute Tx for F and m g / L for k, we get Tx = - (m g / L) x).

Any time we have F = - k x, we have m d^2 x / dt^2 = - k x, which as calculus students will verify has a solution function x (t) = A cos ( `sqrt( k / m ) t).

For a pendulum, the quantity `sqrt ( k / m ) = `sqrt ( (m g / L) / m ) = `sqrt(g / L).

This model is related to the circular model observed at the beginning of class. If we draw to circle of radius A, then if a point on the circle lies at angle `theta, as shown below, it should be clear that the horizontal displacement of this point from the origin is x = A cos(`theta).

Now if `theta = `sqrt(k/m) t (for a pendulum `theta = `sqrt(g / L) t), then the x component is A cos (`sqrt(k/m) t) (for a pendulum A cos(`sqrt(g / L) t).

We see that since `theta = `sqrt(k/m) t, the coefficient `sqrt(k/m) must be the angular velocity `omega of the motion of the point around the circle.

When we are talking about simple harmonic motion we call `omega the angular frequency of the motion. But we visualize `omega as the angular velocity of a point moving around a circle modeling the motion of the object.

The angular frequency is therefore seem to be

`omega = `sqrt(k / m)

(or, for a pendulum,

`omega = `sqrt( g / L) ).

This relationship to central to the understanding and analysis of simple harmonic motion. It relates the force constant k and the mass m to the frequency of motion of the mass (or for a pendulum, it relates the acceleration g of gravity and the length L of the pendulum to the frequency motion).

We close by applying this information to find the length of the pendulum observed at the beginning of class, which has not yet been measured.

We observed that the angular frequency of the pendulum, or the angular velocity of the reference point around circle, was `omega = 2.65 rad/sec. Knowing now that `omega = `sqrt( g / L), we can easily solve for the length L of the pendulum.

The solution is straightforward. We obtain L = 1.39 m.

Measuring L with a meter stick, we obtain L = 140 cm +- 1 cm. The agreement with our theory is impressive.

"