The torque produced by a force on an object is equal to the product of

the distance of the point of application of the force from the axis of

rotation, and the component of the force perpendicular to a line (called the

moment arm) from the axis of rotation to the point of application. Stated

more succinctly in terms of the moment arm, the torque is obtained by

multiplying the length r of the moment arm by the component Fperpendicular

of the force perpendicular to the moment arm:

torque = `tau = Fperpendicular * r.

A fundamental example could be the application of a 20 N force at a

distance of .5 m from an axis of rotation. We implicitly assumed here that

the force is applied perpendicular to the moment arm, so that the torque is

`tau = F * r = 20 N * .5 m = 10 m N.

We use the unit m N instead of N m to designate torque so as not to

confuse it with Joules.

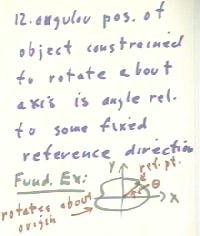

12. What is the meaning of angular position, what is your fundamental

example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

The angular position of an object can be indicated by choosing some

reference point on the object and imagining the radial line from the axis of

rotation to that point. The angular position is then defined by imposing an

x-y coordinate system with its origin at the axis of rotation and the x-y

plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation. The angular position is then

defined as the angle `theta from the x axis to the radial line.

http://youtu.be/zxUDFXmzeUM

13. What is the meaning of angular velocity, what is your fundamental

example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

14. What is the meaning of angular acceleration, what is your fundamental

example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

Angular acceleration is the rate at which angular velocity changes. We

define average angular acceleration as `alphaAve = `d`omega / `dt, as in the

figure below. Angular acceleration is completely analogous to acceleration

as previously defined, except that instead of the change in velocity we use

the change in angular velocity.

A reasonable example would be a situation in which a rotating object

accelerates from angular velocity of 12 radians/second to 20 radians/second

during a force second time interval. The change in angular velocity is 8

radians/second, so the average angular velocity is `alpha = `d`omega / `dt =

8 rad / s / (4 s) = 2 rad / s^2.

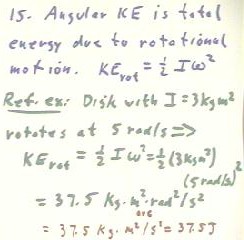

15. What is the meaning of angular kinetic energy, what is your

fundamental example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

Angular kinetic energy is the total energy of motion due to the rotation

of an object, as opposed to the translational kinetic energy, which is the

kinetic energy of the object due to the motion of its center of mass in

three-dimensional space.

Angular kinetic energy is therefore the sum of all the 1/2 m v^2

contributions from all the tiny masses that make up a rotating object. It

can be shown that the total angular kinetic energy is therefore KErot = 1/2

I `omega^2.

As a reference example, a disk whose moment of inertia is 3 kg m^2, when

rotating at 5 radians/second, has rotational kinetic energy KErot = 1/2 I

`omega^2 = ... = 37.5 kg m^2 rad^2 / sec^2. Since the m^2 in the units

refers to a meter of arc (corresponding to the arc of a small mass m at a

distance r from the axis of rotation as we calculate its contribution mr^2

to I), when multiplied by a rad^2 we get a m^2, and the radians drop out of

the units. We therefore obtain KE = 37.5 kg m^2 / s^2 = 37.5 J.

It is clear that angular kinetic energy is an energy and is therefore

measured in Joules.

http://youtu.be/Xw3sKG1VeuY

16. What is the meaning of the unit of gravitational field, what is your

fundamental example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

The unit of the gravitational field is m/s^2, and gives the acceleration

of a freely falling object.

The gravitational field here at the surface of the earth has magnitude

9.8 m/s^2, and is directed toward the center of the earth. At double the

earth radius from the center of the earth, or one earth radius 'above' the

surface of the earth, the inverse square nature of the gravitational field

tells us that the gravitational field will be 1 / 2^2 = 1/4 as great as at

the surface, and will therefore have magnitude 2.45 m/s^2, as indicated

below.

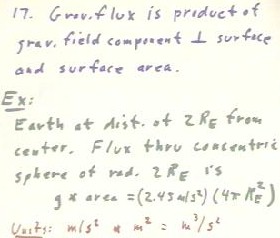

17. What is the meaning of the unit of gravitational flux, what is your

fundamental example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

The flux of any vector field such as the gravitational field (where the

field in each point has both a magnitude measured in m/s^2 and a direction)

is equal to the product of the component of the field through some area.

That is, flux = fieldPerpendicular * area.

The gravitational field here at the surface of the earth has magnitude

9.8 m/s^2, and is directed toward the center of the earth. At double the

earth radius from the center of the earth, or one earth radius 'above' the

surface of the earth, the inverse square nature of the gravitational field

tells us that the gravitational field will be 1 / 2^2 = 1/4 as great as at

the surface, and will therefore have magnitude 2.45 m/s^2, as indicated

below.

Returning to our previous example of the gravitational field of earth at

distance 2 Re from the center of the earth, we imagine a sphere concentric

with the earth at this distance. Since the gravitational field is always

directed toward the center of the earth, it will always be perpendicular to

the surface of this sphere. As we just saw, the field strength at this

distance is 2.45 meters/second^2. The total flux due this large sphere,

whose surface area is 4 `pi Re^2, will therefore be flux = g * area = 2.45

m/s^2 * 4 `pi Re^2. This flux is easily calculated by substituting the

radius of the earth for Re.

We note briefly that this flux is actually negative, since the field

passes through the sphere in an inward direction. We won't worry much about

the sign of the flux in the context of gravitation, but the sign becomes

very important in electrostatics, where we have positive and negative

charges, and in electromagnetism.

The flux of the gravitational field is therefore the product of a

gravitational field (in m/s^2) and an area (in m^2), and therefore has units

of m/s^2 * m^2 = m^3 / sec^2.

As another example of flux, we consider the top of one of the tables

sitting in the lab. The quick measurement shows us that each tabletop is a

rectangle just a little smaller than 1.1 m by 1.5 m, with a total area

approximately 1.6 square meters. The gravitational flux through the tabletop

is therefore g * area, as calculated below.

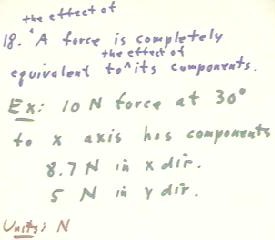

18. What is the meaning of force components, what is your fundamental

example of this quantity, and in what units is it measured?

The components of a force in a plane are two forces, usually in mutually

perpendicular directions, which can completely replace the original force in

their effect.

A fundamental example is a 10 N force at an angle of 30 degrees with the

x axis. Using standard vector techniques, we easily see that the force has

components 10 N cos(30 deg) = 8.7 N in the x direction and 10 N sin(30 deg)

= 5 N in the y direction.

http://youtu.be/F2D1Z79Uu2A

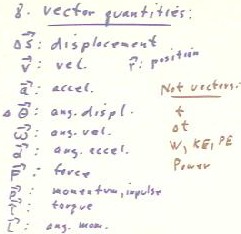

8. What are the vector quantities we study in mechanics?

The vector quantities studied in mechanics include any quantity that is

specified by a magnitude and a direction in space. These quantities include

- position, often designated by r

- the displacement from one position to another, usually designated by

`ds but sometimes by `dy or `dx

- velocity, the rate of change of position with respect to time

- acceleration, the rated which velocity changes with respect to time

- angular displacement `d`theta, the direction of which is parallel to

the axis of rotation, and is determined by the right-hand rule

- angular velocity `omega, the direction of which is parallel to the

axis of rotation and determine by the right-hand rule

- angular acceleration `alpha, the direction of which is that of the

torque producing the acceleration and which changes the angular velocity

vector by adding to it a component `alpha `dt parallel to the angular

acceleration

- force F

- momentum p in the direction of velocity v, or impulse F `dt in the

direction of the force F

- torque `tau in a direction perpendicular to moment arm and applied

force as determined by the right-hand rule

- angular momentum L, parallel to angular velocity, or angular impulse

`tau `dt, which when added as a vector to the angular momentum yields

the new angular momentum

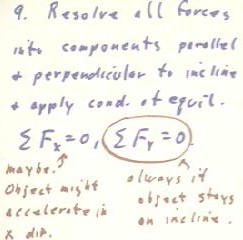

9. How do we analyze the forces that typically act on an object on an

incline?

We first resolve all forces into their components parallel and

perpendicular to the incline. The weight vector will be replaced by

components parallel and perpendicular to the incline, the normal force of

the incline on the object will be perpendicular to the incline, and any

frictional force will be parallel to the incline and in a direction opposite

to the result of all other forces in the direction of the incline. We have y

equilibrium, assuming that there is no external force sufficient to lift the

object off of the incline and provided we assume that the incline is strong

enough to support the object and any forces applied to it.

The normal force will be the equilibrant of all other forces in the y

direction: the plane, if it is strong enough, will exert exactly enough

elastic force to maintain y equilibrium.

It is possible that we also have equilibrium in the x direction,

especially if friction is present. However, if all nonfrictional forces are

not in x equilibrium and if friction is insufficient to overcome the net

result of all other forces, the object will not remain in equilibrium and

will accelerate in the x direction.

10. Why is it that the acceleration of an object on an incline is a

linear function of slope, provided the angle of the incline is small?

On an incline, under the forces of gravity and friction and no other

forces, the forces on object can be expressed by to components in the x

direction and to components in the y direction. In the y direction we have

the weight component -mg cos(`theta) and its equilibrium, the normal force

mg cos(`theta). Parallel to the incline, the forces are the way component -

mg sin(`theta) down the incline and the frictional force f < = `mu | N | =

`mu mg cos(`theta) in the opposite direction.

It follows that when the incline is sufficient to overcome the frictional

resistance, the net force on the object is Fnet = mg sin(`theta) - `mu mg

sin(`theta) directed down the incline.

The second figure below shows that for a small angle `theta, the

hypotenuse of a 'slope triangle' on the incline is very nearly equal to the

run, so that sin(`theta) = rise / hypotenuse is very nearly equal to the

rise / run, or slope, of the triangle. So for small angle we can effectively

replace sin(`theta) with slope.

Furthermore, since the hypotenuse and the run are nearly the same,

cos(`theta) = run / hypotenuse is very nearly equal to run / run = 1. So for

small angle we can effectively replace cos(`theta) with 1.

Thus our net force Fnet = mg sin(`theta) - `mu mg cos(`theta) is very

nearly equal to Fnet = mg * slope - `mu mg. Since `mu and mg are just

constant numbers, this approximate expression for Fnet is a linear function

of slope.

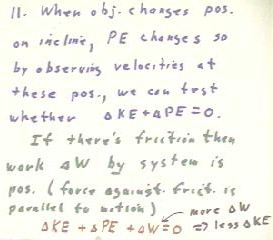

11. How can we observe conservation of energy for objects coasting up and

down inclines?

When an object moves from one position to another on incline, the

altitude of the object, and hence its potential energy, changes. If there

are no external forces other than gravity, i.e., if the object coasts with

negligible friction, conservation of energy predicts that the kinetic energy

of the object will change by an amount equal and opposite to the potential

energy change (so that `dKE + `dPE = 0, or `dKE = -`dPE). We can easily

observe the change of position between two points; if we also obtain

sufficient data to observe the velocity of the object at the two points,

then we can easily determine both the change in potential and kinetic energy

of the object.

If there is friction or some other dissipative force, then the object

must do positive work `dW to overcome this force. In this case, for any two

given positions with their associated change `dPE in potential energy, we

will clearly have a change `dKE in the kinetic energy which is less than it

would be in a the case of no dissipative forces. This conclusion should be

intuitively obvious, at least in the case when the object is rolling down

the incline. It is also confirmed by the conservation of energy equation `dKE

+ `dPE + `dW = 0.

If `dW = 0, then `dKE = -`dPE, and kinetic energy will increase when the

object descends (and its PE decreases) and will decrease when the object

ascends (increasing its PE). If `dW > 0, then `dKE = - `dPE - `dW; since `dW

> 0, -`dPE - `dW is obviously less than just `dPE.

- This implies that if the object coasts down the incline, with a

negative `dPE the otherwise positive `dKE will be less than before and

the object will gain less speed as it goes down the incline (and might,

if `dW is large enough, even lives speed).

- If on the other hand the object coasts up the incline, with a

positive `dPE and therefore a negative `dKE, the -`dW will make the

kinetic energy change even more negative and the object will lose even

less speed then in the no-dissipative-force case.

http://youtu.be/BxWu-CjE5nk

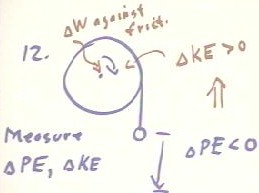

12. How can we observe conservation of energy for the interaction between

descending objects and rotating objects?

By wrapping a string around the rim of a disk and tying a weight to the

free end of the string, we obtain a system which, when released from rest

will experience a loss of potential energy as the weight descends and an

increase in kinetic energy as the wheel picks up speed.

By measuring the distance fallen, we can determine the potential energy

loss of the weight. By measuring or inferring the angular velocity attained

by the disk and its moment of inertia, we can determine the kinetic energy

gained. If the weight is relatively small, its kinetic energy will be

insignificant; otherwise we need to also determine its kinetic energy.

The difference between the potential energy loss and the kinetic energy

gained should be equal to the energy lost to friction in the bearings of the

wheel. This energy can be inferred from the weight necessary to just balance

the friction, so that the disk when given a small velocity will tend to

continue moving at that velocity without speeding up or slowing down. The

potential energy loss of this weight as it descends will be equal to the

energy lost to friction through an equal descent.

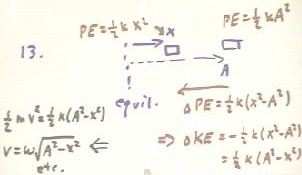

13. How does energy conservation help us understand the behavior of

objects moving in response to linear restoring forces?

At a distance x from the equilibrium position, an object of mass m

subject to a restoring force F = -kx will have elastic potential energy 1/2

k x^2. At its maximum distance A, the object will have potential energy 1/2

k A^2. The change in potential energy from the maximum distance A, where

velocity is zero, to distance x, will therefore be `dPE = 1/2 k x^2 - 1/2 k

A^2 = 1/2 k (x^2 - A^2). Since A > x, this change is negative. The kinetic

energy change `dKE = -`dPE will therefore be 1/2 k (A^2 - x^2).

The velocity of the object at this position will therefore be the

velocity v at which KE = 1/2 m v^2 = 1/2 k(A^2 - x^2). Solving for v we

obtain v = `sqrt( k/m ) `sqrt(A^2 - x^2) = ... = `omega A `sqrt( 1 - (x/A)^2

), as shown in recent class notes.

http://youtu.be/5-GSM4v3HXo

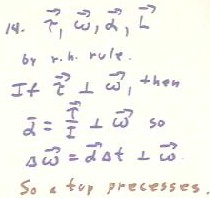

14. What is the

direction of the torque, angular velocity, angular acceleration and angular

momentum vectors, and how to these quantities interact as vector quantities?

The directions of these vector quantities are found by the right-hand

rule, as outlined in #8 above.

We note here that if the torque `tau is perpendicular to the angular

velocity `omega, then since the angular acceleration `tau / I is parallel to

the torque, our change in angular velocity `omega will be `alpha `dt

perpendicular to `omega. The angular velocity vector, and hence the angular

momentum, will therefore change in a direction perpendicular to the angular

velocity or angular momentum.

This phenomenon

explains why a top precesses.

http://youtu.be/NGvTb5JD8J8

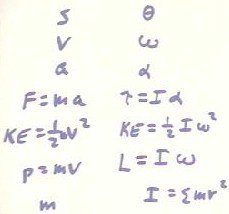

15. What are the analogies between angular quantities and linear

quantities?

The equations of kinematics, Newton's Second Law, mass, and momentum all

have analogs for their rotational counterparts, and nearly all defininitions

and relationships between the standard quantities hold for the corresponding

rotational quantities.

- Angular position `theta is analogous to position s.

- Angular velocity `omega is analogous to velocity v.

- Angular acceleration `alpha is analogous to acceleration a.

The relationships of kinematics can be reasoned out for the angular

quantities exactly as for the standard quantities, so our standard equations

of kinematics can be directly translated into the equations for angular

kinematics.

Newton's Second Law is expressed as F = ma, or for angular quantities as

`tau = I `omega, where

- Torque `tau is analogous to force F.

- Angular acceleration `alpha is analogous to acceleration a, as

observed before.

- Moment of inertia I (the sum of all mr^2 contributions) is analogous

to mass m.

Kinetic energy KE = 1/2 I `omega^2 measures the same quantity as KE = 1/2

m v^2. Both quantities are measured in the same units, and is possible to

convert angular kinetic energy directly to linear kinetic energy and vice

versa.

Angular momentum L

= I `omega is analogous to momentum p = mv, but the two quantities are

different and not interconvertible (there units, for example, are different,

with the units of angular momentum being kg m^2 / s, has opposed the units

of momentum which are kg m/s.

(note: this material was discussed as part of video clip #02)