"

Physics II, 4/28/99

Atomic Structure; Dual Nature of Light

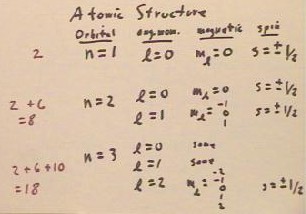

The structure of an atom is largely governed by the values of the orbital, angular

momentum, magnetic and spin quantum numbers of its electrons. Every electron in an atom

must have a different combination of these four numbers.

By observing the relationships of the energies of electrons emitted when light

shines on certain metals as a function of the wavelength and intensity of the light, we

conclude that light delivers energy to the electrons in discrete amounts that depend on

the wavelength but not the intensity of the light. This behavior is consistent with the

behavior of particles but not of waves. We thus conclude that light sometimes acts as a

particle beam (with particles called photons having energies E = h f), and sometimes as

waves exhibiting diffraction effects and other wave properties. It has also been observed

that electron beams in certain circumstances exhibit wave behavior with wavelength `lambda

= h / (electron momentum) (this wavelength is called the deBroglie wavelength).

We can begin to understand atomic structure in terms of the quantization of four

quantities, the combination of which must be different for every electron in the atom.

- Each quantity is governed by a quantum number.

- The quantum numbers of an electron include:

- the orbital quantum number (the n that arises from the quantization of angular

momentum),

- an angular momentum quantum number having to do with the shape of the probability

distribution of the positions of a given electron,

- a magnetic quantum number which dictates the alignment of the electron orbit with an

external magnetic field, and

- a spin quantum number which dictates the alignment of the electron itself with an

external magnetic field.

The distribution of quantum numbers is governed by a few simple rules:

- The angular momentum quantum number may be any whole number less than the orbital

quantum number n.

- The magnetic quantum number may be any integer whose magnitude is less than or equal to

the angular momentum quantum number.

- The spin can be + 1/2 or - 1/2.

Using these rules we see that if n = 1, the angular momentum quantum number must be 0,

so that the magnetic quantum number (which has magnitude less than or equal to that of the

angular momentum quantum number) must be 0.

- There is therefore only one choice for these three quantum numbers.

- Since there are two choices for the spin quantum number, there are two possible

combinations for the n = 1 electrons.

The n = 2 electrons have the choice of angular momentum quantum numbers 0 or 1.

- If the angular momentum quantum number is 0, then the magnetic quantum number must be 0,

so that again there are only two choices for the quantum numbers.

- If the angular momentum quantum number is 1, then the magnetic quantum number can be -1,

0 or 1 and with the two possible choices for the spin quantum number we see that there are

6 possible combinations.

- Thus for n = 2 there are 2 + 6 = 8 possible combinations of quantum numbers.

A similar analysis works for the n = 3 orbital, with 2 and 6 possible combinations for

angular momentum quantum numbers 0 and 1, respectively.

- Angular momentum quantum number 2

is also possible, which gives rise to possible choices of -2, -1, 0, 1 or 2 for the

magnetic quantum number, and hence adds 10 possibilities for a total of 18 possible

combinations of quantum numbers.

Video Clip #01

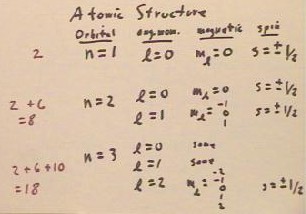

When single-wavelength light is shined on certain types of metal, called photoelectric

metals, there is a tendency for electrons to be emitted from the metal.

- The energies of these electrons can be measured by a setup such as that indicated in the

figure below.

- A wire mesh is maintained at a negative voltage with respect to the metal, tending to

repel the electrons that escape the metal.

- An electron therefore must have a certain kinetic energy to reach the grid.

- Upon reaching and passing through the grid, the electrons are collected on a metal plate

(not shown) and allowed to flow back to the photoelectric metal.

- By measuring the current of the electrons flowing back to the metal, we can measure the

rate at which electrons having sufficient energy to overcome the potential of the grid are

emitted from the metal.

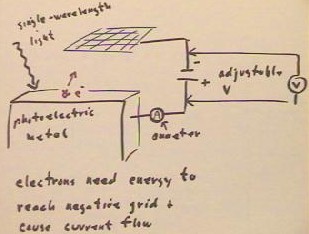

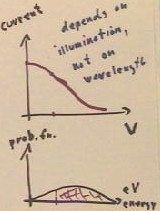

According to the wave theory of

light, brighter light should give electrons whose energy distribution peaks at a higher

energy.

- Thus more intense light should

eject higher-energy electrons from the metal, and for a given grid voltage the number of

electrons reaching the negative grid should increase continuously with the intensity of

the light.

- As the grid voltage is increase,

the observed current should therefore change in the manner depicted in the currect vs. V

graph.

- For a given voltage, the rate at

which electrons flow should thus be proportional to the area under the probability

distribution function for energies, starting at that given voltage (indicated for one

particular voltage in the graph at bottom right).

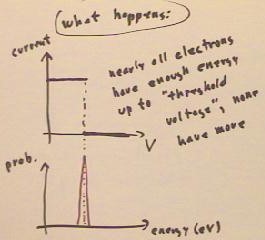

What is actually observed what is actually observed is that the current remains

constant up to a certain 'threshold voltage', indicating that practically all electrons

have an energy very nearly equal to that corresponding to this threshold voltage.

- The probability distribution

function is thus confined to energies very close to this threshold voltage, and we

conclude that the light imparts very nearly the same energy to every electron emitted.

- This energy does not depend on the

brightness of the light.

- Brighter light gives a higher

current, indicating that more electrons are emitted, but the threshold voltage does not

depend on the brightness.

Video Clip #02

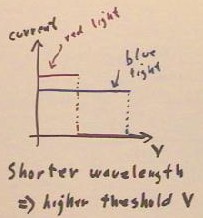

The threshold voltage does,

however, depend on the wavelength of a light. Blue light results in a higher threshold

voltage then red light.

- Shorter wavelength light implies a

higher threshold voltage, indicating that shorter wavelength light imparts greater energy

to the electrons.

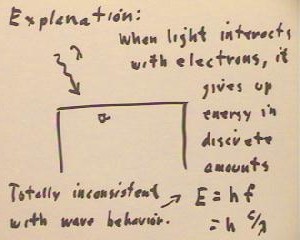

The conclusion drawn by physicists is that when the light interacts with the electrons

the gives up energy in discrete amounts, with the energy equal to the product of Planck's

constant h and the frequency f of the light wave.

- Since the frequency of the wave is inferred from the speed of light and the wavelength

(as measured by, say, diffraction gratings), we note that this energy could also be

written as E = h c / `lambda.

All this is totally inconsistent with any theory of wave behavior.

- It is as if the light is formed

from discrete particles, with the energy of each particle dependent only on the wavelength

of the light.

- But particle streams should not

exhibit wave behaviors such as refraction and interference effects.

- We are left with the uncomfortable

conclusion that light sometimes behaves as particles and sometimes as waves, and with a

sense that our intuitions about particles and waves is of little use in understanding

light.

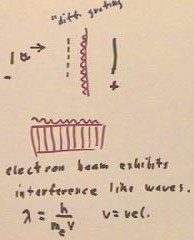

If light with its wave behavior can sometimes act like a particle beam, then we might

expect that particle beams might be able to exhibit wave behavior.

This is in fact the case.

- An electron beam aimed at a

'diffraction grating' consisting of layers of atoms in a crystal exhibits interference

effects just as do light waves.

- The wavelength observed for a beam

of electrons is `lambda = h / ( electron momentum ), where the momentum of the electron is

the product of its mass and its velocity.

Video Clip #03

"